Am I a heartless wretch? Was Georgia O'Keeffe? Are all artists heartless wretches?

Still on my lives of artists kick

As promised, moving on from Van Gogh to Georgia O’Keeffe. Check out all the Van Gogh essays, here.

In a letter she wrote from the house in upstate New York where Georgia O’Keeffe initially spent summers with her husband, Alfred Stieglitz, she describes herself as “drowning in green.” She did not like the lush landscape of Lake George. She did not like sharing the space with Stieglitz’s loud and boisterous family. She tried to stake out the solitude necessary to paint there. She fixed up a shed, far from the main house and other buildings filled with Stieglitz’s family.

But people still found her there. Children knocked on her door. Alfred came by along with countless visitors. “I don’t know why people disturb me so much—they make me feel like a hobbled horse,” O’Keeffe wrote. Her husband loved a loud and busy life. O’Keeffe did not.

O’Keeffe was forty-two years old and had been married for five years when she finally asserted herself and said no to summers in Lake George. Her letters suggest it was a hard decision and not one Stieglitz exactly approved of. The dynamic was complicated by Stieglitz’s infatuation with a series of younger women, but even with these betrayals, O’Keeffe agonized over the decision. “I think I only crossed him when I had to—to survive,” O’Keeffe wrote. She loved her husband deeply, even as she needed a different sort of life.

Did Stieglitz give permission for her to go to New Mexico? Did she feel she needed his permission? When she left, did she believe she was leaving for the summer or forever? It might not have been clear to either of them, but, still, she went.

Here’s how things tend to go in a small town. You tell someone you’re a writer. Someone else says they know someone who’s also a writer. You find yourself sitting in a coffee shop with a complete stranger talking about writing.

This is how I met Marla Sink Druzgal many year ago. She’d come to Madison for her husband’s work. We sat across from each other at the plush red chairs they used to have in the coffee shop, the setting for so many important conversations in my life.

“You have to be serious about your writing,” Marla told me. When people came to visit her, she explained that even while they were visiting, she would have to spend time writing. She didn’t care if people thought it was rude to leave them alone like that. Writing was her job and it had to get done. Did that make her a horrible host? A horrible friend? She did not care.

Turns out that no one much comes to visit my husband and I, so whether or not I would leave my guests alone to go write has never been a question. When the two of us travel, I have aspirations to write that never come to fruition. When we travel with a group of people, writing becomes my safe haven in a world of too much noise. Writing is where I go to remember who I am.

For most of the rest of their marriage, until Stieglitz died at 82, O’Keeffe made her trek to New Mexico every summer while Stieglitz went to Lake George. Stieglitz seemed to have mostly come around to the idea. Still, O’Keeffe often described herself in letters as a “heartless wretch” in part because of this arrangement. She could not stay in Lake George, as a good and dutiful wife should. Her decision to leave branded her. She was cruel. Heartless. Greedy. Selfish.

These are things that to some extent, every artist must be at one time or another. At one point or another, as an artist, you will have to shut the world out in order to go to the place where the art gets made. No one can go there with you. You will have to build your own studio shed or flee to New Mexico. At some point, you will have to say to the people who have come to visit you, “No, I have to write now.”

Here’s a funny story. When my not-yet-husband and I were discussing the timing of when he and his daughter would move into my house with me, I suggested that we delay until the manuscript for the sociology of gender textbook I was writing at the time was done. It would be hard, we reasoned like the reasonable people that we were, to write with a seven-year-old in the house. We had zero idea at that point exactly how hard it would be to merge our lives. Our main concern was my textbook. It all feels so naïve in retrospect.

For years after, in the fantasies where I got a huge advance for one of my books, I spent the money on a writing space. A studio. A little shotgun shack of a house somewhere in town where I could go to write. My writing space for most of the years my daughter was in the house was a desk in our bedroom. Or the coffee shop.

I made it work, but I also dreamed of a space apart. A whole other building all to myself. I applied to writer’s retreats, but I never got accepted. I understand why O’Keeffe went all the way to New Mexico. Sometimes people are disturbing, like a hobble, getting in the way of the freedom of movement that art sometimes requires. I get it. I am, yes, the tiniest bit envious.

O’Keeffe loved the landscape of the Southwest. She had ever since she’d taught in Texas. It was the world she wanted to paint, not the lush forests of Lake George. She was born in Sun Prairie, Wisconsin, also not a place that was particularly full of trees. Maybe this love of wide open spaces was implanted in her from the get-go and that’s simply reflected in her art.

I am a child of wooded hills. Of gentle river valleys. When I step into a forest, my body relaxes. I breathe easier. If I am drowning in green, it’s a welcome feeling. In the town where I live, I feel gently held in the cup of the green valley walls that surround me.

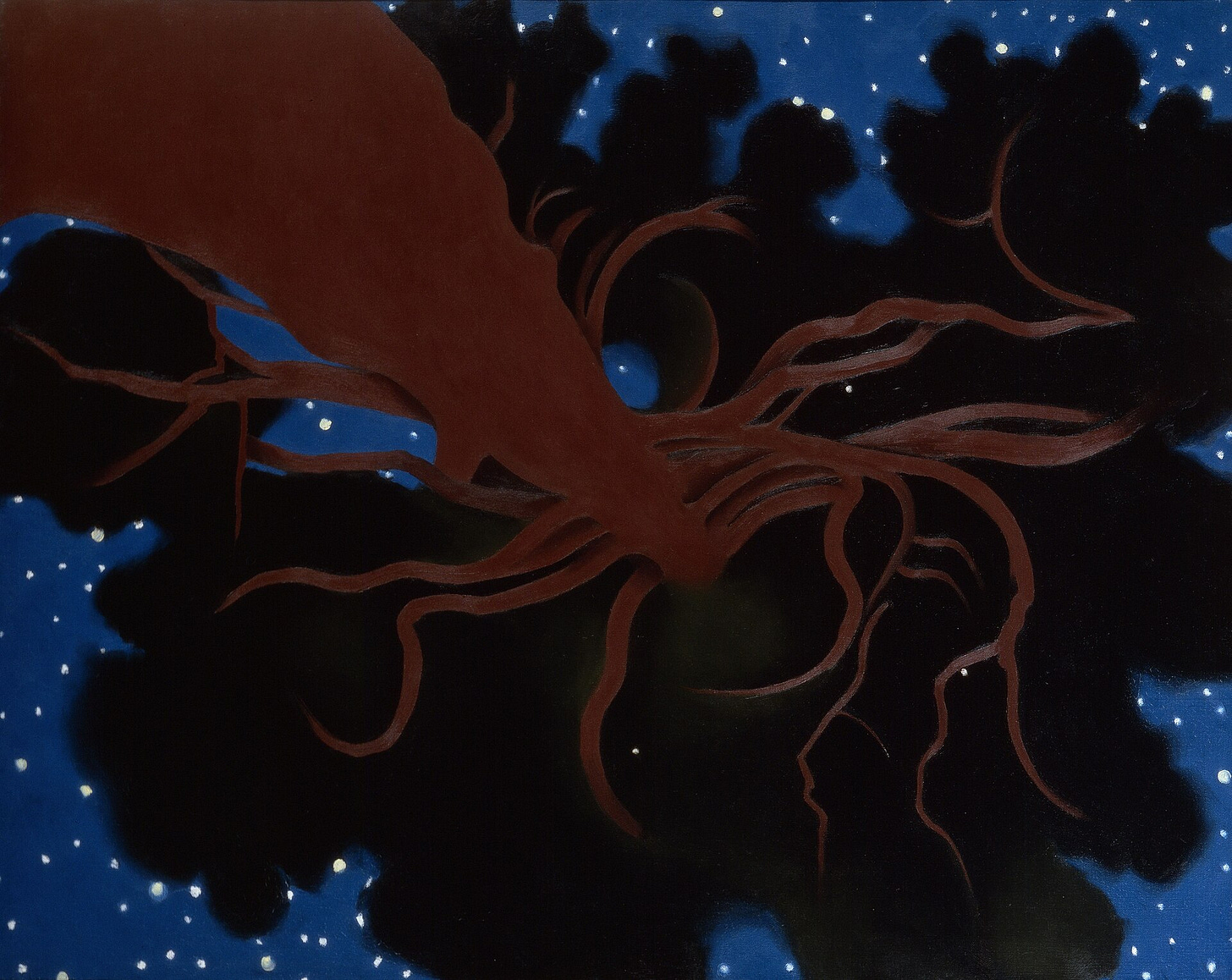

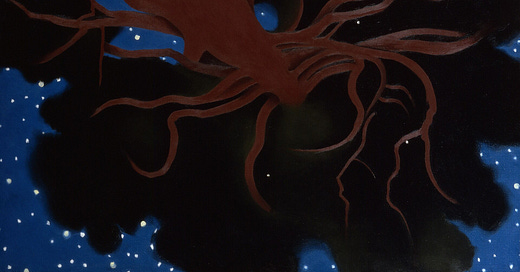

But I also admit that when I sit down to draw or paint the wooded hills around me, it’s…frustrating. There’s so much going on. Of course, you cannot capture very single leaf. Or maybe you could, but I don’t have the patience for it. Maybe O’Keeffe didn’t, either. Reading about her disdain for Lake George makes me wonder if trees aren’t, in the end, harder to paint than spare desert landscapes.

Maybe woods are too busy to easily capture. Too raucous. Too demanding. Maybe the trees for her were like the constant stream of people, demanding something from her which she could not or was no longer willing to give.

It's clear in the case of both Van Gogh and O’Keeffe, that if they could not paint, they went a little crazy. Okay, perhaps in both their cases, they went a little bit crazy even when they could paint. But the work—the art—it was a compulsion. They could not stop. Even when O’Keeffe lost her sight, she tried to use people as her brush, squinting at the canvas with what sight she had left as she instructed them where to place the paint.

I try to avoid the romantic ideal that great art comes from great suffering. I believe you can be both psychologically healthy and also produce great art. I also wonder about this compulsive need to make art and what it means. I feel it, too, this itchiness if I haven’t written in a while. The unsettled sense that comes when I don’t have a project I’m working on. I am happiest when I’m immersed in a manuscript. I’m happiest when I’m lost in creating a world on the page.

What is that about? Is it just another kind of addiction? Is it its own kind of mental health problem? Should there be a category for compulsive artist in the DSM? I’m not writing out of a place of unhappiness, but I might need the writing to be happy. Is that a good thing?

There have certainly been moments in my marriage when I’ve felt like a “heartless wretch.” I’ve also felt like a horrible mother. And a horrible daughter. A horrible friend. Sometimes it has to do with my writing, but mostly it’s just life. Let’s be honest, I spend a lot time feeling like a fairly horrible person, which has very little do with my writing or with the people in my life and a lot to do with the emotional baggage I bring to adulthood.

I have felt cruel. Greedy. Selfish. Yes, heartless, too. I have been all of those things at one time or another. I can be difficult. Prickly. If I had the success that Georgia O’Keeffe had achieved fairly early in her life, I wonder if I’d be even more difficult. Even more prickly. I wonder if success doesn’t afford you the space to be more selfish in service of the work. I wonder if it doesn’t make it that much easier.

O’Keeffe and Stieglitz were together until his death. She never remarried. Their marriage was rocky and often chaotic, but with Stieglitz gone, O’Keeffe gradually withdrew farther and farther into herself. This isolation left her vulnerable at the end of her life to manipulation by a young man who may have convinced O’Keeffe that they were married in order to gain control of her estate. There’s an irony in the fact that O’Keeffe, who so bravely asserted her independence earlier in her life, later lost it to vulnerability, old age, and a self-imposed loneliness.

Of course, Georgia O’Keeffe was not a heartless wretch. She was a person, just like the rest of us, in possession of a heart that was both needy and delicate. Both fierce and scared. Both craving love and fearing the limitations a life in communion brings with it. She was not a heartless wretch, or at least no more or less than the rest of us.

Thanks to all the new subscribers for joining us here! If you love this post and others like it, consider hitting that Tip Jar button above and buying me a cup of coffee in appreciation. Or even better, become a paid subscriber.

In SEX OF THE MIDWEST news, I just got some awesome new author photos from Joey Ernst at Freewheel Studios. He’s local and took what is probably the best picture ever of my husband and I, in the middle of bidding on a cake at the Madison Main Street Gala.

We’ve got many book-related events in the works, here in Madison and farther afield, so stay tuned for that schedule and for the pre-order link. In the meantime, interior book design and cover design are ongoing. I know, making a book takes a loooong time.

Oh this is so relevant for so many of us!

Wonderful, insightful essay. And yes to all those feelings around writing. I've got them, too. Especially love this: Writing is where I go to remember who I am.