The first day of classes last week didn’t get off to the best of starts. The sidewalks between my regular parking lot and the building where I teach were all blocked off by construction, which resulted in me climbing through some very slippery landscaping. With my bad knee, I thought I might slide down the slope and perish before the semester even began. Then when I got to my classroom, the temperature was hovering about 78 and would reach a peak of 81 by Wednesday, temps that make for less than ideal learning conditions.

Despite all that, when I finally got to my classroom building it was all good. I love the first day of the semester, when hope is still high. I love walking in the door and seeing the faces of all the new students and wondering what they’ll be like. They’re all terrified to some degree or another. They’ve been on campus for a week and maybe they’ve decided their roommate is okay or their roommate is a complete horror show. Maybe they’ve already bonded with their sports teams, which often get on campus early. Or maybe their teammates are all assholes and they hate the coach.

All of them have surely had visions and expectations about what college will be like and some of those expectations will collide violently with what it’s like now that they’re finally here. Some of their backpacks are full of notebooks and pencils and an elaborate planner with markers in multiple colors to block off different events and deadlines. Some of them come to class with their phone and nothing else. Some of them have already read the syllabus and some of them never will.

Some of the students will compensate for the anxiety and uncertainty of being a new person in a new situation by diving into classroom discussion, raising their hand at every opportunity and with such enthusiasm, I’m afraid they’ll dislocate their shoulder. Some will respond to the same set of emotions by hiding in the back of the room with a look of total disdain on their face. Or a look of total boredom. Or a look of deep confusion. The expression doesn’t really matter. After twenty years of teaching, I can say with 95% certainty that whatever their face happens to look like, what they’re really feeling is some level of abject terror.

It's not this terror that makes me love the first day of class. It’s realizing that in time, that terror will fade. The students will settle in. They’ll figure out that, at least in the case of my classes, there’s not really much to be afraid of. I’m going to do my level best not to humiliate them or embarrass them or torture them. If at all possible, I’d like for us to have fun.

With time, I’ll know with more certainty what’s behind those facial expressions. I’ll get some small glimpse into the chaos that is part of all of their lives. On that first day, I already love my students, even without knowing them. I love their vulnerability and their bravery. I love their insecurities and their fears. I look into their faces and I see myself as a first-year student, hundreds of miles away from anyone I know, in a whole different culture, trying to figure out how the hell to fit in. I see my daughter on her first day almost five years ago now.

It took me a while as a teacher to learn to center all of that when I look at my students. It took me years to come to see them as amazing bundles of contradiction and fragility, instead of as sources of infinite annoyance who didn’t even own a writing instrument. It took a pandemic to solidify all those insights into a sort of teaching mantra—do no harm. Be a safe place. I know it sounds sappy, but, yes, lead with love.

Seriously, you might ask. Am I really claiming to love my students? Am I saying that I love all my students? Even the one who will use AI to write their first paper? Or the student who, halfway through the semester, will inform me that they had no idea they were supposed to be doing a journal for every class, after they’ve already missed most of them?

I recently read Lori Gottlieb’s amazing memoir, Maybe You Should Talk to Someone, about her life as a therapist and her own experiences as a patient of therapy herself. There are a surprising number of similarities that jumped out between therapy and teaching. Not that I’m a therapist to my student. The very the idea horrifies me.

But Gottlieb talks about how therapy that isn’t face-to-face and in the same space is almost impossible do do. Over Zoom, it might be possible to see a person’s facial expressions and maybe even pick up on some physical cues, but it’s still not the same. There is an energy that exists when you are physically in the same room with someone that will never be captured on Zoom and the same is true of teaching.

I think what Gottlieb is describing is the fact that in any sort of social interaction between people, the interaction itself takes on a life of its own. That’s the energy we’re feeling. When I’m in a room with my students, the class as a group becomes a thing, with its own energy and trajectory and, I don’t know, intentions? That energy is more than the sum of each individual in the class. It is its own thing and it doesn’t happen when you’re on Zoom. I also happen to believe that energy of togetherness and interaction is fairly essential to learning.

Also in Gottlieb’s memoir, someone asks her if she likes all her clients. She says, yes, she finds a way to like all of her clients because she gets to know them in all their complexity. It is very difficult for us as humans to despise someone whom we also know intimately. That’s what I believe, anyway. If you know someone intimately, you see them in their weakest moments. You see their vulnerabilities and their fears. You see, in other words, that they are very much like you. That might not make them your favorite person ever, but it makes hatred pretty difficult.

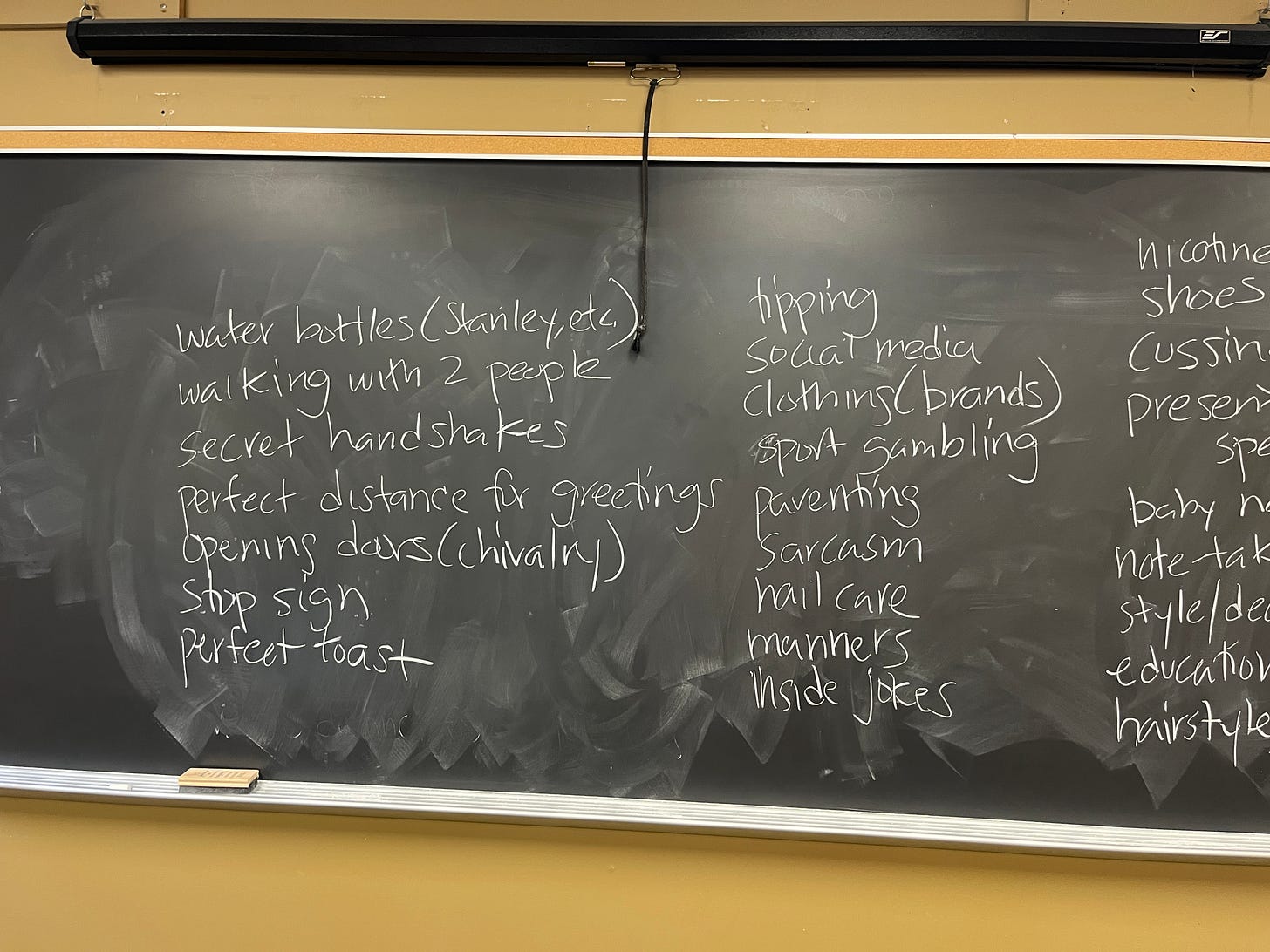

I don’t get to know my students with the same level of intimacy with which Gottlieb gets to know her clients. But you’d be surprised at the things we learn about each other in an introduction to sociology class. I already know that one student is a good cook. That another student is very much resisting a nickname some random fellow student is trying to give him. I know one of my students has thirteen siblings. I know where they’re from (which in my book, is an important part of truly knowing anyone). This is all after week one. This is all after three classes…a little more than three hours spent together.

There’s a moment in the memoir when Gottlieb very much wants to know if her own therapist likes her. Who doesn’t want to know that? There’s something so unbalanced about the therapist/client relationship. We tell therapists all these deeply intimate things. What if, knowing all of that ugly underside, they don’t like us?

Her therapist, Wendell, answers that, yes, he likes her. He likes her Neshama, the Hebrew word for spirit or soul. She gets what he’s saying instantly.

When I read that, I immediately thought of my students. That’s it, I thought. That’s right. I love their Neshama. Or as Gottlieb goes on to say, I love “their tender places, their bravery, their soul.” I love them for being here. I love them for showing up in whatever way they’re able to. I love them for their foibles and their victories. I love them for that fear that vibrates just under the surface on the first day of class but which most of them will conquer and overcome and take a big step into a different (and hopefully) better version of themselves. I love them for that potential.

I guess I could do what I do without loving them. I also know that I don’t really want to try.

“That’s what I believe, anyway. If you know someone intimately, you see them in their weakest moments. You see their vulnerabilities and their fears. You see, in other words, that they are very much like you. That might not make them your favorite person ever, but it makes hatred pretty difficult.”

Truth.

And that’s why we always want to divide and dehumanize. That’s why we call another group cockroaches, so it’s easier to hack them to death with machetes. Even if we’ve lived as neighbors for generations, and are joined through marriages but we belong to different groups, when we take away their humanity, it is so much easier to round them up and ethnically cleanse our part of the city by executing their men and boys, and raping their wives and daughters.

I see so many variations of “reThuglicans” and “DemonRats” even here on Substack. Divide and dehumanize. Some posts on Notes are like drive-by shootings dripping with hate. It’s some primitive evil deep inside us that we too often choose to give into. It is a choice to give into it. We can choose otherwise.

Robyn, I really appreciated this essay about how you see your students. To know them, even a little, is to love them, or like them, or be willing to go out of one’s comfort zone to tolerate them and maybe even to try to understand them.

Carry on. The world is a better place because of your attitude. Thank you.

Your writings today, Robyn, have warmed the cockles of my heart.