So, of course, I’ve been thinking about what I can do in the face of the onslaught of attacks on transgender people by this Republican administration, as well as the many Republican administrations at a state-by-state level. Sometimes I forget that I have written quite a bit about these topics. Sometimes I forget that I have some expertise on these topics.

Specifically, in my book Throw Like a Girl, Cheer Like a Boy, I have several chapters that deal with gender in sports. It’s a very accessible book and I’d love it if you went out and bought it or checked it out of your library.

But I wrote the book (as well as my other nonfiction book about gender, She/He/They/Me: An Interactive Guide to the Binary) to get information about gender to a wider audience, so, fuck it. If this isn’t a wider audience, what is?

This week, I’m going to post chapters from that book that deal with gender and sports. This chapter is about the case of transgender athletes. It discusses some of the history of transgender athletes, as well as the issues faced by athletes who are nonbinary or gender fluid. If you identify as neither a man nor a woman, where do you compete? I think this is yet another argument for ending gender segregation in sports altogether. Stay tuned for the next chapter on gender differences in athletic ability if you’re not convinced.

Some of this info is dated as the laws and rules are constantly shifting. But if you’re looking to educate yourself about gender and sports, this is a good place to start and stay tuned for the next chapter later this week.

In 2012, athlete and filmmaker Lauren Lubin moved to New York City and took up running. Lauren (who uses the pronouns they/them) had moved to the city to work on a documentary, “We Exist,” about the experiences of non-binary and gender-neutral people, those like Lubin who do not identify as either male or female. Lubin started running as a way to get out of the apartment in a city where they didn’t know anyone, but what started as an escape soon turned into a passion. Lubin registered for their first race in 2014 and immediately the strict rules and gender segregation of sports limited them. As Lubin stood on the starting line of their first event, one of the organizers proudly proclaimed that running was an event for everyone. All the other runners cheered, but not Lubin. “I was like, ‘No!’ Running is not a sport for everyone. Running is a sport for two types of people,” Lubin said.[i] Those two types of people? Women and men.

If you’re a cisgender athlete, or someone for whom the gender you were assigned at birth matches the gender you feel you are, you might not notice all the ways in which the gender binary is an integral part of sports. But if you’re outside that binary, like Lubin, the deeply gendered nature of sports is impossible to ignore. In the case of running a race, everything from registration to the type of gear provided identifies runners as either female or male. Non-binary runners like Lubin are forced to put themselves into a category—male or female—that doesn’t represent their sense of who they are. They must literally pretend to be someone else in order to participate. “There I was, unable to run as the person I really am,” Lubin said. “Forced to either sit at the sidelines or run under a false identity in order to participate.”[ii]

Two years later, Lubin ran in the New York City marathon as the first-ever gender-neutral athlete in the event’s history. It’s a small step, but doesn’t address the mountain of barriers that face all gender non-conforming athletes, trying to find a way to fit into the gender-segregated world of sports. The deeply gendered nature of sports causes problem for many intersex athletes, as we discussed in Chapter 2. Gender testing of women in international sports competition continues to result in the disqualification and humiliation of women who are naturally born with some sort of ambiguity in their biological gender. This gender testing takes place in the interests of maintaining a strict gender segregation in sports, as discussed in Chapter 3. This segregation is based on a firm belief in the athletic superiority of biological males—a superiority that is supposedly based in their genetics, hormones, and/or anatomical structure. As we’ve explored in previous chapters, the evidence for men’s un-qualified athletic superiority is hardly an established fact. Still, all these dynamics converge in the experiences of transgender athletes, who are forced to figure out how to fit themselves into a sport world firmly built on the foundation of the gender binary.

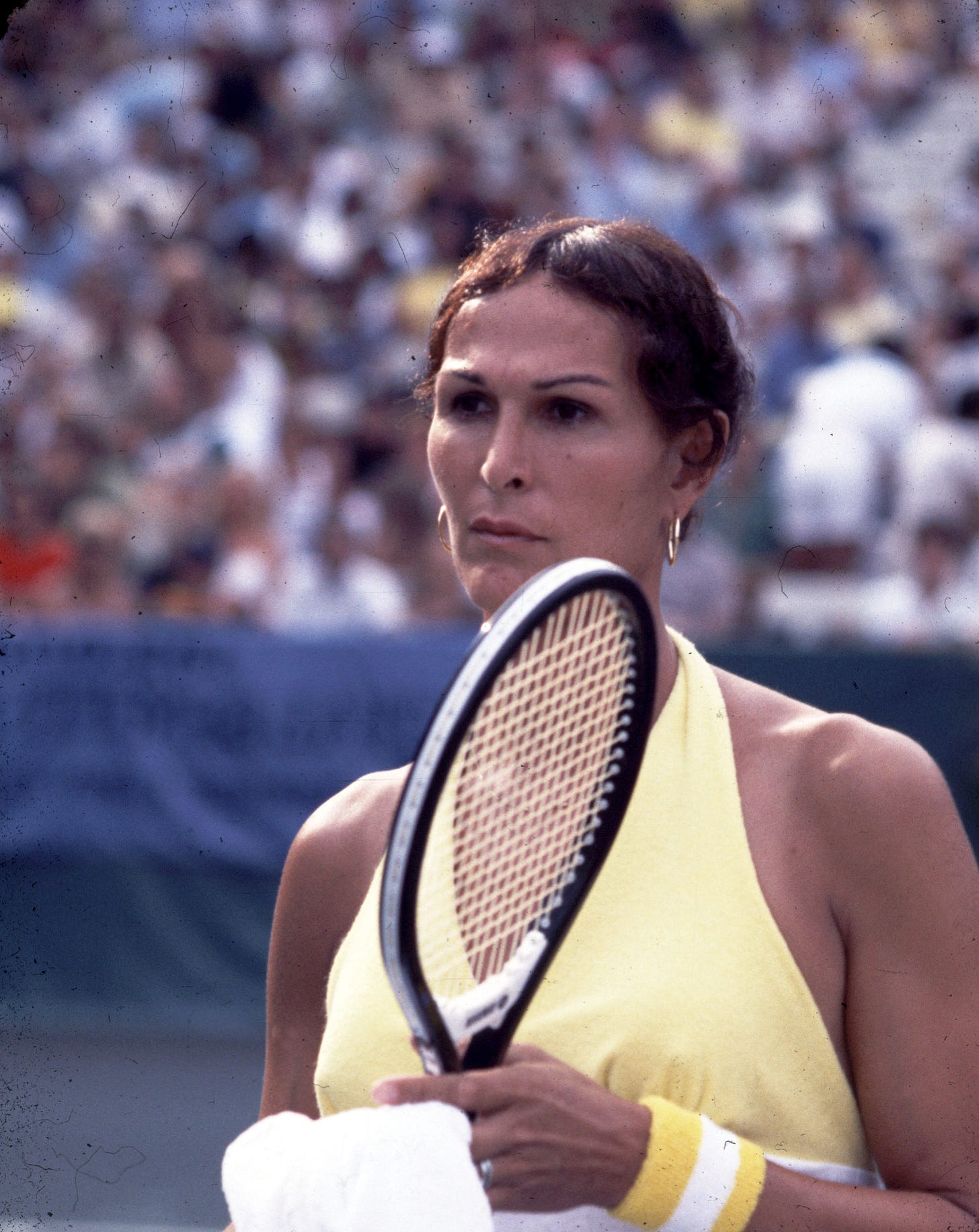

Renée Richards’s right to play

In 1976, the United States Tennis Association announced they would introduce a gender test for women. They were ten years behind organizations like the International Olympic Committee (IOC) and the International Association of Athletics Federation (IAAF). The move was motivated, not by a generalized fear of men trying to pass themselves off as women, but in response to one specific person—Renée Richards.[iii] Richards was born Richard Raskind instead of Renée and with his distinctive left-handed serve, he had been captain of the Yale men’s tennis team, dominated the all-Navy tennis championship and won a New York state tennis title. In 1975, Richards underwent gender confirming surgery and became Renée. The next year, Renée won a California tournament, playing under the name Renée Clark. But her serve was recognized by a spectator and she made the evening news because of her transgender status. A week later, the U.S. Tennis Open introduced a chromosome test, purposefully geared to prevent Richards from competing as a woman.[iv]

Richards was fortunate to have the money, earned in her successful medical career, to fight back against the United States Tennis Association’s (USTA) policy. Like many transgender athletes who would come after her, Richards wanted to be able to go on enjoying tennis and saw no reason why that shouldn’t be possible. Richards sued the USTA over their gender testing policy. The arguments used by the USTA lawyers echoed the nationalist fears used by the IOC and IAAF ten years earlier to establish their own gender testing policies. One lawyer referred to the “world-wide experiments, especially in the Iron-Curtain countries, to produce athletic stars by means undreamed of a few years ago.”[v] The comment had nothing to do with Richards’s specific case but demonstrates the moral panic that existed around patrolling gender boundaries in sports.

Richard’s case went all the way to the Supreme Court, where the justices ruled that the gender test was “grossly unfair, discriminatory and inequitable, and a violation of her civil rights.”[vi] Legal scholar Pamela Fatiff, in an analysis of the USTA and IOC testing policies, found that gender testing infringed on U.S. citizens’ Fourth amendment right to privacy, as well as breaching the individual’s right to equal protection under the law. At the 1977 U.S. Open, Richards, competing in the women’s events, lost to Virginia Wade in the first round of the singles competition, but reached the finals of the women’s doubles before finally losing.[vii]

The fear of trans women athletes

Beyond the specter of Cold War, genetically-modified, super-athletes from behind the Iron Curtain, the fear raised by Richards’s case centered on an imagined stampede of men trying to pass themselves off as women in order to gain a competitive advantage in women’s sports. Almost thirty years later, those fears persist. Most recently, Martina Navratilova, a longstanding advocate for the rights of lesbian athletes, controversially shared her belief that trans women have an inherent advantage over cis women.[viii] Navratilova wrote in a 2018 op-ed,

“A man can decide to be female, take hormones if required by whatever sporting organization is concerned, win everything in sight and perhaps earn a small fortune, and then reverse his decision and go back to making babies if he so desires. It’s insane and it’s cheating.”[ix]

Ironically, Navratilova had been coached by Renée Richards, after having been beat by her in a doubles match. Though she later apologized, Navratilova was subsequently removed from her position on the advisory board of Athlete Ally, an advocacy group for LGBTQ athletes. Her statement demonstrates the fear and hostility that exists toward trans women athletes.

As we discussed in Chapter 2, there have been no documented cases of men doing what Navratilova proposed—temporarily passing themselves off as a woman in order to compete in women’s sporting events. In fact, given the gross disparities in the amount of economic rewards and recognition women receive in their sports relative to men, it’s hard to imagine what would motivate a man to do so. As we discussed in Chapter 3, any “fortune” women win from sporting events is indeed very, very small relative to men. Given that men are supposed to be able to easily beat women in all athletic competitions, it’s unclear what sort of ego boost a man would get from winning in a women’s event. It’s difficult to brag about something you were already assumed to be able to do.

Navratilova’s comments also equate being transgender with a superficial putting on and taking off gender identities in order to “cheat” at sports, an accusation that is deeply insulting to transgender individuals who face real, life-threatening struggles as they work to line up the gender they were assigned at birth with who they truly are. Obviously, the hurtful and inaccurate nature of these comments doesn’t stop organizations and individuals from continually raising the specter of men disguising themselves as women in order to gain an unfair competitive advantage. With the growing number of openly transgender individuals at all levels of sports competition—from high school to amateur races to professional teams and international events—organizations have had to develop policies to accommodate transgender athletes within this gender-segregated terrain. Those policies reflect the same concerns about male athletic advantage, with no concern about the patrolling of men’s sports.

In 2003, the International Olympic Committee (IOC) instituted their first policy on transgender athletes. The rules stipulated that transgender athletes could compete only after they’d had gender-confirming surgery, followed by two years of hormone therapy.[x] This meant transgender athletes would be forced to take a two-year break from competition. It also left no room for the many transgender athletes who might not want gender-confirming surgery. As some critics pointed out, the policy could be read as pushing a form of institutionalized genital mutilation on transgender athletes.[xi] It was also unclear what having or not having male or female genitalia had to do with athletic ability. In 2016, the IOC modified their policy, abandoning the surgical requirement for the participation of trans athletes. Trans men, or female to male (FTM) athletes, are now eligible to compete in men’s event with no restrictions at all. Male to female (MTF) or trans women athletes, on the other hand, have to provide proof that their testosterone levels have been below a certain cutoff level for at least a year prior to competition.[xii]

In line with what we saw in Chapter 2 with the case of gender testing, the IOC’s policy is much stricter when applied to women’s sports than on the men’s side of things. Just like intersex women, the “problem” with transgender athletes is focused around the question of how to prevent trans women from gaining a competitive advantage against cis women. This concern is echoed in the National Collegiate Athletic Association (NCAA) guidelines on transgender athletes, where the rules for trans women athletes are again different than those for trans men athletes. Trans men may compete as men regardless of whether they’re taking testosterone or not. If they are taking testosterone, they need a medical exception and aren’t allowed to compete on a woman’s team. Trans women, on the other hand, have to go on competing as women until they’ve completed one calendar year of testosterone suppression treatment. For trans women who choose not to undergo testosterone suppression treatment, they are prohibited from competing on a women’s team. Trans men who do not undergo hormone treatment, on the other hand, can compete on either men’s or women’s teams.[xiii]

The small but growing research being done on trans women athletes suggests that for those who undergo hormone therapy, there is no competitive advantage when they compete as women.[xiv] But what about trans women who don’t pursue hormone suppression treatment? These policies force the broad spectrum of ways to be transgender into narrow, limiting categories. Some trans women may pursue hormone suppression treatment as part of their transition, but others may have no desire to do so. These policies leave no options for trans women who do not alter their hormone levels to compete. They force trans women into a certain way of being transgender which may not fit their unique sense of themselves.

Mack and Andraya: the case of two transgender athletes

At the level of high school competition, policies on transgender athletes vary wildly in the United States. Take the case of two transgender athletes, competing in two different sports in two states with very different policies dictating how they compete. Mack Beggs is currently a redshirted wrestler at Life University in Marietta, Georgia. While in high school, Beggs was forced to wrestle against girls even though he is a transgender boy. He won the 110-pound girls state championship two years in a row in Texas, where state policy dictates that transgender athletes compete as the gender listed on their birth certificate. Even though Mack was taking low-doses of testosterone and wanted to compete against other boys, state policies prevented him from doing so. It was only after graduating from high school that Mack was finally able to compete against other boys, where he won third place in the junior division of the U.S.A. Wrestling’s Greco-Roman and freestyle divisions.

Texas’s policy prevented Mack from competing as his correct gender as well as drawing objections from parents and others who felt the fact that Mack took testosterone gave him an unfair advantage. Andraya Yearwood, at the other end of the spectrum, is a runner and a trans girl who competes in Connecticut. The policy in that state allows transgender athletes to compete as their affirmed gender identity with no conditions, making it an example of one of the most open policies regarding transgender sports participation. That doesn’t mean athletes like Andraya don’t still face discrimination and hostility. Immediately before her race in the 2018 state open, two women confronted and harassed Andraya, calling her a boy and then shouting at her, “Why are you even on the team! Why are you here?!”[xv] Andraya still took second place in the race, but then had to face parents yelling profanity at her from the stands, with some of the kids coming to her defense.

As a black transgender girl, Andraya is especially at risk of being a victim of violence. There’s an ongoing epidemic of violence against transgender people, with twenty-six deaths in 2018. Mainstream media became aware of this trend in April of 2019 with the case of Muhlaysia Booker, who was attacked by a mob and then murdered a month later in Dallas, Texas. Eighty-one percent of the murders of transgender people in 2018 were committed against trans women of color and by July of 2019, more than 10 trans women of color had been murdered, victims of transmisogynoir, or the specific hatred of transgender women of color who sit at the intersection of three interlocking systems of oppression—sexism, cissexism and racism.[xvi] All of this makes Andrya’s parents especially concerned for her safety.[xvii] She’s somewhat protected within the bubble of her small, Connecticut town, but in June of 2018, parents began circulating a petition to change the state policy regarding transgender high school athletes. The new policy, circulated by parents of female track athletes in a neighboring town, would require that transgender students compete as the gender they were assigned at birth. In order to compete as their affirmed gender, students would have to undergo hormone replacement therapy.

As the cases of Andraya and Mack demonstrate, policies on transgender athletes vary widely from state-to-state. Six states (Hawaii, Mississippi, Montana, South Carolina, Tennessee and West Virgina) have no policy on the participation of transgender athletes, leaving each school district or high school to set their own rules. With no set policy, transgender students are subject to the whim of whatever particular school officials might be in power. Nine states have policies that are outright discriminatory (Alabama, Arkansas, Idaho, Indiana, Kentucky, Louisiana, Nebraska, North Carolina, and Texas). In these states, participation is determined by the gender listed on an athlete’s birth certificate or high school athletes must have gender-confirming surgery with a hormone wait period before they can participate as their gender identity. Another seventeen states (Alaska, Delaware, Georgia, Illinois, Iowa, Kansas, Maine, Michigan, Missouri, New Mexico, New York, North Dakota, Oklahoma, Ohio, Oregon, Pennsylvania and Wisconsin) have a mix of policies that, while they aren’t outright discriminatory, still present significant hurdles for the participation of trans athletes. Trans athletes are dealt with on a case-by-case basis in some of these states, with subjective criteria being used to decide which gender students can participate as. In some of these states, policies mirror those of the NCAA, requiring that trans women athletes undergo a year of testosterone suppression before they can compete as women.[xviii]

Policies that require athletes to undergo medical intervention are problematic at the collegiate level, but they’re especially dangerous for high school athletes. This has to do with high school athletics and the timing of puberty. Doctors generally recommend that transgender children not undergo any medical intervention before they hit puberty. Rather, prior to puberty, most doctors and experts recommend pursuing a gender affirming strategy with gender-expansive kids. Gender-expansive is an umbrella term for all children who do not conform to their culture’s expectations for boys or girls. Transgender kids can be gender-expansive, but not all gender-expansive kids are transgender.[xix] In a gender affirming strategy, family and friends support a social transition for the child. This might involve: letting their child wear clothing and hairstyles appropriate to their affirmed gender; letting their child choose a gender-appropriate name; asking others to use the pronouns consistent with the child’s affirmed gender; and using bathrooms and other facilities that match their gender identity.[xx] Because medical interventions like hormone treatment and surgery are either irreversible or can have serious, long-term side effects, most experts recommend delaying any medical therapy until after puberty, reserving these procedures for older adolescents. The logic is to allow gender-expansive kids as much time as possible to explore their gender identity before any irreversible steps are taken. High school policies which mandate that transgender athletes undergo hormone treatment or surgery contradict the treatment recommendations of both the American College of Osteopathic Pediatricians and the American Academy of Pediatrics.[xxi]

In addition to going against expert recommendations, a policy requiring high school students to medically alter their bodies before competing as their affirmed gender makes little sense from a competitive standpoint. There are fewer gender differences in the bodies of children before puberty. At these ages, boys are not, on average, significantly taller or stronger or bigger than girls. Most of the differences in hormone levels, a concern reflected in the NCAA policy, don’t emerge until after puberty. Given that these differences are already smaller in athletes before puberty, it makes no sense to institute a policy that requires them to permanently alter their bodies.

Other experts criticize these restrictive policies from a broader perspective that considers the purpose of high school sports. At the collegiate level, athletic scholarships are at stake, as well as the considerable amount of money that colleges and universities receive from their elite athletic programs. At the level of professional sports, as well, we can argue that athletes get paid to win. Perhaps if it makes sense at all to patrol against unfair competitive advantage, it would make the most sense at the collegiate and professional levels, where the stakes are higher and money is part of the game. But shouldn’t a large goal of high school sports be to learn core values like hard work, teamwork, determination and inclusion?[xxii] Research tells us that playing high school sports has a wide range of benefits for student-athletes. Sports are important to developing self-esteem and a connection to both school and community. Time spent on the field or on the court also serves as a deterrent to the use of alcohol, drugs, tobacco and other unhealthy behaviors in children and teens.[xxiii] Transgender children and teens are especially vulnerable to harassment and bullying from their classmates. And when they are threatened or assaulted, they’re likely to receive no help from teachers, coaches and other adults in authority.[xxiv] More than half of all transgender youth attempt suicide before their twentieth birthday.[xxv] These are exactly the type of students who might most benefit from participation in sports, and yet, research reveals that discrimination prevents many of these students from participating.[xxvi] If high school sports should be about having fun and learning to work together, any competitive advantage that trans athletes, and specifically trans women, have should be secondary to the goal of inclusion.

Transphobia and locker rooms

That trans girls would have a competitive advantage over cisgender girls in competition is just one of the fears that drives the policy of many high school athletic programs. This belief contributes to the stereotype discussed in Chapter Two and Three that all male bodies will perform better athletically than all female bodies. Of course, this isn’t the case. As we’ve discussed, there’s a great deal of overlap in the abilities and skills of girls and boys.

Another fear that underpins high school policy toward trans girls is the belief that transgender girls are really boys, despite their affirmed gender identity. This essentialist viewpoint might claim that trans girls are not “real” girls in the way their cisgender counterparts are. This transphobic view denies the experiences of trans girls, whose gender identity is just as real as that of cisgender people. This fear is closely related to the concern expressed by some high school authorities and parents that transender girls pose a danger to their teammates and competitors. This “danger” takes several different forms. For some, the fear has to do with what happens on the court or the field. Transgender girls, from this perspective, pose a danger to their cisgender teammates because they’re bigger, stronger and unable to exercise adequate body control. All of these are argued to cause an increased risk of injury to other athletes.[xxvii] This fear ignores the fact that athletes who are taller, stronger and have less control over their bodies compete against other athletes all the time in our currently gender-segregated world. On every court and field, there are differences in size, strength and ability. The only exception would be sports like wrestling, where weight classes control for differences of size. Allowing trans girls to compete with cis girls, then, doesn’t radically alter the existing status quo in high school sports.

For some officials and parents, though, there’s a different sort of fear around the participation of trans girls in sports—what happens in the locker room. These concerns echo the larger conversations in society about transgender people’s right to use bathrooms that match their gender identity. The discussion clusters around two issues—safety and privacy. As far as safety goes, those opposed to trans girls using the girls locker room assume that transgender people themselves are a threat to cis girls.[xxviii] These fears circle back again to the belief that trans girls and trans women aren’t “real” girls or women, but men in disguise. As men, they constitute a threat to the sexual and physical safety of cis girls and cis women.

There are several weaknesses with this line of thinking. As researchers have pointed out, these arguments prioritize anatomical gender over gender identity. Because trans girls were born with male bodies, they are seen as dangerous regardless of their gender identity is. These arguments presume that bathrooms and lockers room are sexual spaces, but specifically heterosexual spaces. In these spaces, anyone with a male genitalia is inherently dangerous. Anyone without male genitalia is a potential victim. This narrative is both wrong and deeply insulting to women and men. Not all men—cisgender or transgender—are potential sexual predators in waiting. Not all women—transgender or cisgender—are passive victims destined to be the victims of violence.[xxix] From this perspective, allowing trans girls and trans women to use women’s locker rooms and bathrooms has the added danger of making it easier for cis men who are sexual predators to prey on women in bathrooms, even though there’s no empirical evidence that this is true. Of course, there’s also nothing preventing cis men from preying on women in bathrooms and locker rooms under current systems of gender segregation. Simply having a sign on a door that says “women” does nothing to prevent men from going inside.

A slightly different concern about locker rooms has to do with issues of privacy. Privacy is a real concern in the open layout of many locker rooms, with communal showers and large, undifferentiated changing areas.[xxx] But privacy is a concern for all students, not just transgender athletes. Many children and teenagers, regardless of their gender identity, would prefer not to be exposed in the ways common in locker room settings. A solution that would help both transgender and cisgender students would be to build different sorts of locker rooms—locker rooms designed with privacy in mind. Existing locker rooms could be retro-fitted inexpensively with privacy screens. This approach supports not just transgender athletes, but all students with a preference for privacy.[xxxi]

Being non-binary in a binary world

Current policies regarding transgender athletes, even the most open, assume a certain way of being transgender. That is, they assume that a transgender person is someone whose gender identity is still masculine or feminine. A trans woman or a trans man can still logically compete as a woman or a man. But what about transgender people who are non-binary (people whose gender is neither male nor female)? Or genderqueer (someone who feels that their felt gender doesn’t fit the socially constructed norms for their biological sex), or bigender (someone who identifies with two genders) or agender (someone who feels they lack gender, are genderless, or don’t care about gender identity)?[xxxii] People with these identities feel they are neither masculine nor feminine. Or they might feel they are some combination of both. Or they might feel like their gender is something else entirely. Where would athletes like these compete? What place is there for athletes like Lauren Lubin, with whom we started this chapter? Research suggests that the number of people who are non-binary or genderqueer are growing, especially among younger generations.[xxxiii] How will these athletes be included in a sports world that is still firmly grounded in a binary system?

No sports organization currently has a policy that includes provisions for non-binary or genderqueer athletes. Athletes like Lauren Lubin and G Ryan, a genderqueer swimmer who competes for the University of Michigan, are forced to forge their own paths through a binary system. G Ryan (who uses they/them pronouns) competes for the women’s team, though team members refer to themselves as “Team 43” as a way to linguistically embrace the diverse gender identities of its members.[xxxiv] Ryan helped to install gender-inclusive restrooms and a gender-inclusive intramural recreation building on campus. They argue that sports organizations should allow non-binary and genderqueer athletes to compete for whichever team they choose. Other ways to be more gender-inclusive include: using more trans- and non-binary-inclusive language; relaxing uniform requirements, which are often challenging for anyone who doesn’t fit the gender norm; and building more restrooms and locker rooms that are gender-inclusive.[xxxv]

Should sports be gender-free?

Obviously, another solution is to relax or abolish the strict gender segregation of the sports world. As we’ve discussed in previous chapters, there are several arguments in favor of de-segregating sports. From a historical perspective, we can compare the current gender segregation of sports to the racial segregation of sports which existed in the United States prior to the middle of the 20th century. Prior to Jackie Robinson breaking the color line in baseball, many of the arguments in support of racial segregation in sports echo those we hear today about gender segregation. Those opposed to integration argued that black players were inferior because they were inherently less intelligent than white athletes. These beliefs in lesser intelligence were based in racial science of the time that has since been proved wrong. In addition, scientists and other experts argued that black players didn’t have the necessary endurance and stamina to compete with their white counterparts. This was again rooted in scientific racism which posited that African-Americans as a race were feeble and physically inferior to the white race. Left to their own, in fact, racial scientists predicted that African-Americans would die out altogether because they were so physically weak as a race.

Obviously, these predictions were wrong on many counts. As we’ll explore in Chapter 8, racial science today is more likely to argue for the inherent physical superiority of black athletes, though this would be just as incorrect as previous arguments about black feebleness. Few people today would argue in support of a system of sport structured along racially segregated lines, even though at the time, the system appeared completely natural. Is there truly a difference between our past system of racial segregation and today’s gender segregation in sports? Are there ways in which the science being produced in support of the continued segregation of women and men might be influenced by prevailing cultural assumptions in the same way past racial science was?

As with the case of racial segregation in sports, there are real gains to be had from de-segregating sports along gender lines. Seeing Jackie Robinson and other trailblazers who came after him compete on America’s playing fields had measurable effects on racial attitudes in the United States. Research suggests that de-gendering sports could have similar effects. When boys and men play sports with girls and women it has the potential to change their views about what girls and women are capable of. Especially many all-male team sports help to create and reinforce toxic forms of masculinity. De-segregating sports would provide one less location in which toxic masculinity might flourish.

There’s much to be gained from a world in which women and men play together. This is especially true for transgender athletes. What’s the potential cost? One of the most consistent objections is that sports competition that was gender-integrated would no longer be fair. Men would have an unfair advantage over women. As we’ve discussed, this would only be true for some women and some men. There are many women who can run faster, jump higher, or throw farther than many men. But another question we have to ask is, what exactly do we mean by fairness? Are sports really fair in the first place?

If you start making a list of all the ways in which sport competition isn’t particularly fair, you’ll end up with a pretty long list. We can start with the all the unfair advantages that have nothing to do with biology or physical ability. Take the case of Renee Richards discussed at the beginning of the chapter. The USTA worried that Richards had an unfair advantage because she was assigned as masculine at birth. But they weren’t concerned about all the advantages Richards had due to her privileged upbringing—going to a private prep school, graduating from Yale, completing medical school, having a successful surgical practice which facilitated her access to the world of highly competitive, elite tennis.[xxxvi] As a sport traditionally associated with white, upper class, people tennis is still less accessible to non-white, poor people around the world. Social class is an important component in both access to and success in all sports because playing sports usually costs money. Sport participation is expensive because of the cost of fees, uniforms and equipment. With today’s explosion of youth travel teams in the United States, sports costs money in the time and expenses it takes to get children to games, practices and matches. At the elite level of any sport, the athletes who are still around are there because of a cascade of unfair advantages they’ve been given due to their social class.

Add to social class all the other ways in which some athletes have advantages over others. Peyton Manning and Eli Manning, two highly successful NFL quarterbacks, had an advantage in the form of a father who also played in the NFL, providing his own insight and knowledge. In fact, in many men’s professional leagues participation is passed down through family lines. Is it fair that Ken Griffey, Jr., a Hall-of Fame baseball player, got to learn how to play from his father, a three-time All-Star? Is it fair that NBA star Steph Curry probably benefited from the knowledge and connections his father, Dell Curry, had collected during his own extensive NBA career?

To this list of the ways in which sports isn’t fair based on social factors, we can add all the other inequalities of size, speed and ability that have nothing to do with gender. There are only a handful of sports which try to account for these physical differences in order to ensure a measure of fairness, usually based on weight class. In boxing, it’s deemed unfair for a 126 pound featherweight to compete against a 200-plus pound heavyweight. Most other sports have no size or weight restrictions on athletes. On the basketball court, is it really fair to allow Brittney Griner, at 6 feet, 8 inches, to compete against Leilani Mitchell, at 5 feet, 5 inches?

In many ways, sports aren’t really fair. If fairness isn’t at stake in the gender de-segregation of sports, what is? Some critics suggest that the real reason we cling to the necessity of gender segregation isn’t fairness, but rather our need to reinforce the idea of gender in the first place. In a world that is increasingly gender integrated, where the strict roles laid out for men and women are loosening, sports remains one of the last strongholds of difference. Yes, women may be able to be CEOs and hold political office and even run marathons. But they cannot beat men and they cannot play with men. Not because it would be unfair, but because it would further call into question the meaningfulness of gender as a category.

Sport for everyone?

Some transgender athletes have found success within the gender-segregated sports world. In 2016, Chris Mosier became the first transgender athlete to make the Team USA roster in the sprint duathlon.[xxxvii] According to IOC meeting records, two other transgender athletes competed in the 2016 Olympics, though they chose to do so anonymously. Two transgender athletes—Laurel Hubbard and Tia Thompson—have set their sights for the 2020 Olympics in Tokyo.[xxxviii] Still, when Mosier competes in North Carolina, the bathroom bill (HB2) prevents him from being able to use the bathroom, a telling echo of the experiences of many African-American athletes who competed during the Jim Crow ear in the American South. Activists like Lauren Lubin and Chris Mosier are hopeful that the Olympics will soon acknowledge the existence of non-binary athletes, a first step toward their inclusion and toward making sports at all levels truly open not just to women and men, but to everyone.