Sort of desperate for something to watch a few weeks ago, my husband and I binged Manhunt, an only okay-ish series about the search for John Wilkes Booth. The show was clearly trying to be too many things at once—exciting hunt for a fugitive along with historical drama about the post-war chaos caused by Lincoln’s assassination. Mostly what I thought as I watched the show was, “Are they making this up?” Like Booth was really part of a Confederate conspiracy? I didn’t know that. My knowledge of U.S history has gaps wide enough to drive a house through.

So when I saw a novel called The General and Julia at the library I picked it up, trying to plug some of that gap with a novel about Grant looking back on his life as he’s dying in New Jersey and feverishly working on his memoirs (which were, incidentally, published by Mark Twain’s publishing company because, big surprise, Mark Twain was also fed up with traditional publishing).

From that novel I learned that Grant was born in Ohio, just miles from the Ohio River. He also went to school for a while in Maysville, Kentucky, the town my father commuted to for work for a period of years and right down the road from where my aunt and uncle lived in Brooksville. Also the general area where the Clooney’s hail from.

In other words, in the novel I discovered that Grant was my people. Because really the whole Ohio River valley is one continuous place, regardless of what side of the river you’re on. That’s my theory, anyway.

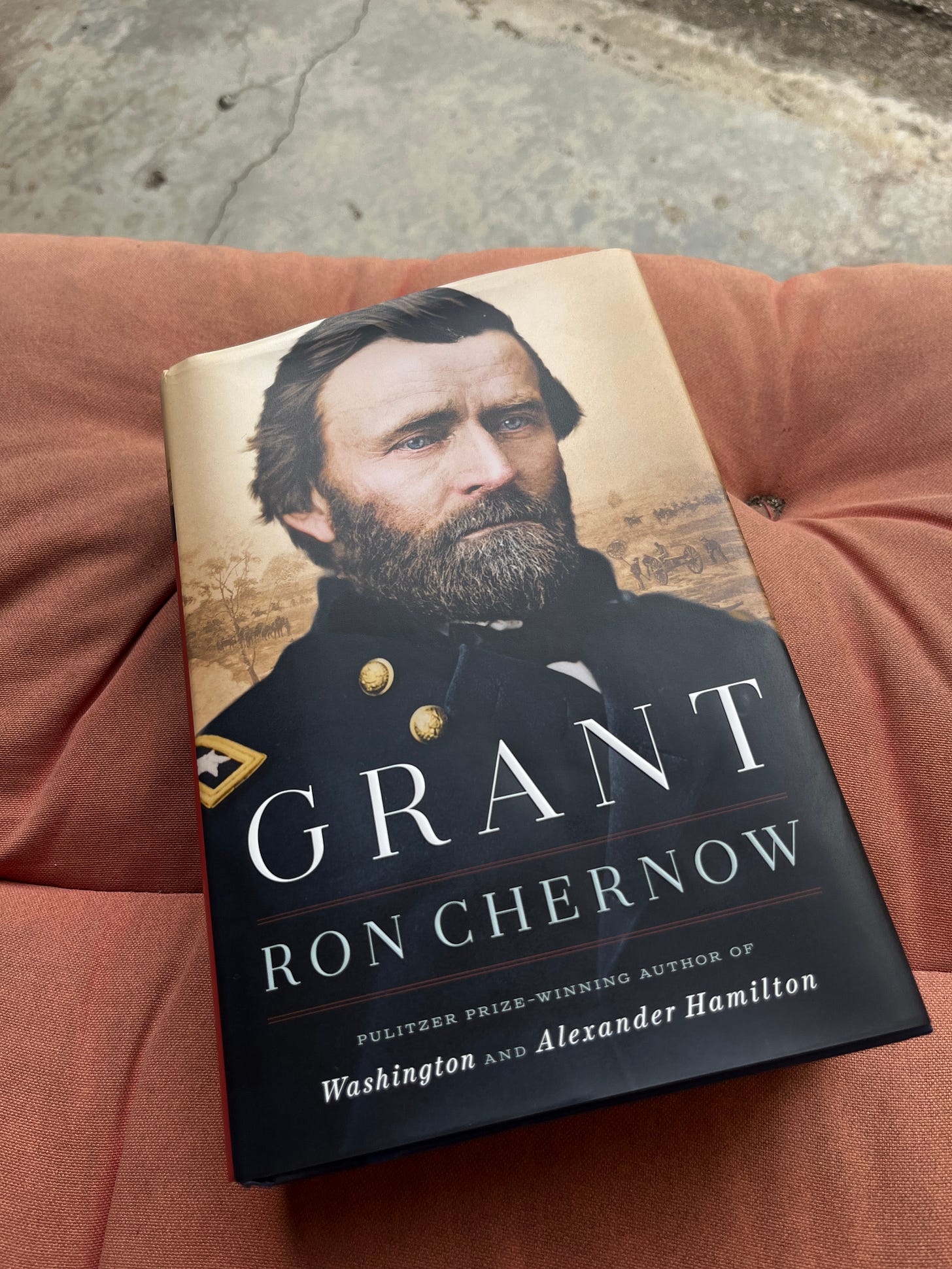

Then I bought Dan Chernow’s biography of Grant and settled in to read all 900+ pages. This is a semi-regular summer activity for me. I like to sink into very thick books in the summer. Sometimes it’s a Brandon Sanderson fantasy. Sometimes it’s one of Chernow’s biographies. Basically reading books that long is like taking up residence with a set of people or a place or a world. So you could say Grant and I moved in together for the last week or so.

I learned many things about Grant, most of which I will probably soon forget because that’s how my brain works at this point. I learned a lot about the post-Civil War period. Grant was a champion of Reconstruction and the full incorporation of freed people into American society. I’d always had the sense that someone dropped the ball with Reconstruction, even if I didn’t know who or how. Now I wonder if there was ever any other way it could have gone. The Civil War ended slavery but white folks in the South had no intention of allowing Black people to be free and equal citizens. The only way to compel them to do so was by military occupation with Federal troops, which doesn’t exactly change hearts and minds.

In a lot of ways, the resistance of Southern states to the full enfranchisement of Black people hasn’t changed even now. Mississippi has the largest percentage of Black population in the country at 39%. But between 10 and 15 percent of those Black people are disenfranchised in the state, deprived of their right to vote due in part to that continuing legacy of Reconstruction along with draconian laws about felony convictions and voting. That’s 130,000 Black people in Mississippi who cannot vote.

One of the most interesting tidbits from the book was Grant’s perspective on the electoral college and race. Before the passage of the 13th, 14th and 15th amendments, Black people in the South counted only as 3/5 of a person, which meant fewer electoral college votes for Southern states because of lower population counts.

After the Civil War, Black people counted fully as part of the population but were still disenfranchised. Yes, technically it was legal for Black men to vote, but they were prevented from voting not by laws, but by violence. Brutal, organized, systemic violence to keep Black people from voting. Just during Grant’s presidency, thousands of Black people were murdered in the South to ensure that they would not vote. Black men were murdered along with women and children. This violence wasn’t random, but carefully planned in order to make voting too dangerous for the Black population.

This means that after the Civil War and still today many Southern states get electoral college votes based on their total population even though significant portions of that population are not actually able to vote. Their power to determine presidential elections is based in the numbers of Black people in their states, even though many of those Black people are prevented from voting. The electoral college is, in other words, deeply racist and deeply fucked up.

That’s certainly not a revolutionary thought. But reading the Grant biography made me think, what if the number of electoral college votes each state received was based not on their total population, but on the percent of their population that actually votes? What if you got rewarded with more political power for making it as easy as possible in your state to vote? What if there were incentives to increase voter turnout?

Of course, this is mostly an interesting thought experiment. In the U.S., one party is invested in getting as many people as possible to vote and the other party is not so much into that. This is a very strange situation, but there we are.

The other thing I learned in the Grant biography was that in the late 19th century, politicians formed political parties willy-nilly. The Whigs sort of became the Republicans. But then when some Republicans got miffed, they went off and started their own convention with a new party. Next election, they did it all over again. Also, party conventions were in Cincinnati most of the time, which, why?

Maybe starting a new party was easier back then because the party system was less institutionalized? The barrier to forming new parties in the U.S. in the past seemed to be money, but in the age of internet fund-raising, what prevents a new party from raising some big bucks? Imagine a party whose central platform was the climate and reducing poverty. How awesome would that be?

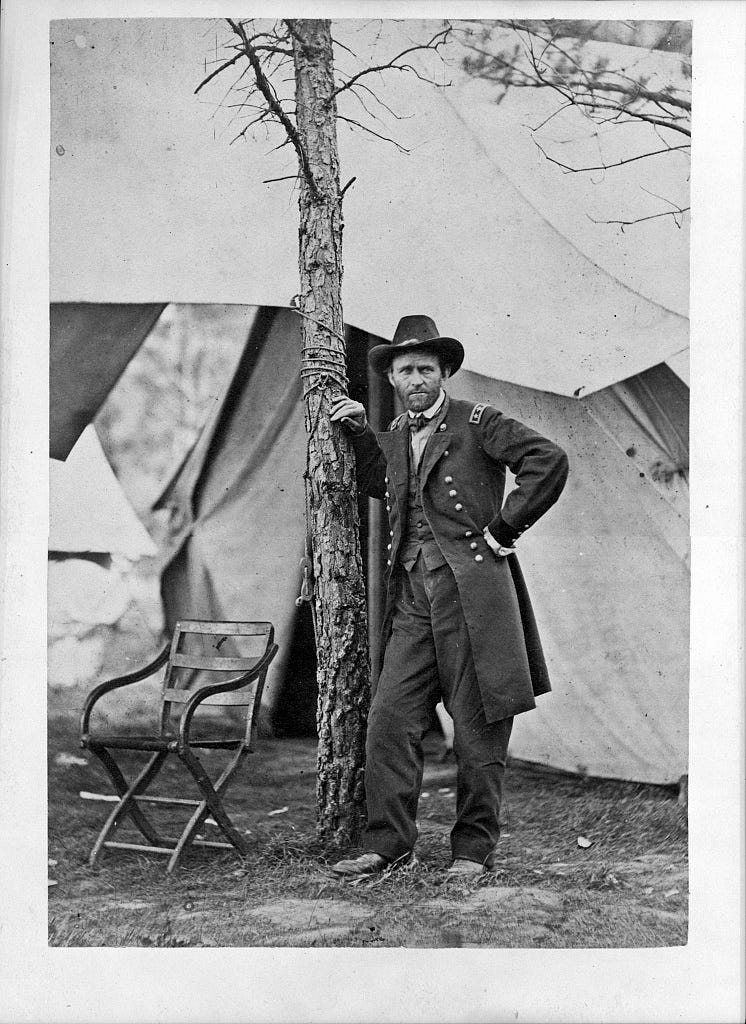

I finished the Grant biography yesterday and already I miss him a little bit. He was a man who loved his wife and family deeply. People made fun of him and Julia for holding hands. Fuck people. As a president, he was too trusting at times. It was hard for him to imagine that people might be duplicitous and scheming. He was mostly humble and the image of him showing up at Appomattox Courthouse in a dirty, dingy uniform is a pretty good image of who he was. He was a Midwesterner. He was from the Ohio River valley. He’s my people.

Sadly, the story/essay/thing I wrote, “George Clooney, Do You Miss Augusta,” is no longer at the literary magazine where it was published, though if you follow this link, you can see the awesome artwork by Nusha Ashjaee that went with it. So for your special reading pleasure, here’s the story/essay/thing I wrote.

George Clooney, Do You Miss Augusta?

It’s not completely outside the realm of possibility that George Clooney and I could meet. We’re both Kentuckians. He went to Northern Kentucky University for a while, which is where almost everyone I went to high school with ended up. It’s where I went to take the SAT. George Clooney and I have both stood at the center of that campus and felt like we were trapped inside a concrete fortress made by people with cold and barren souls.

What I’m saying is, in some ways, our paths have already crossed. So it doesn’t take much to imagine some kind of social gathering we might have in common. Maybe he’s back in town for some event to honor Nick, his dad. Maybe we’re both waiting in line at the cash bar and he starts the conversation.

“Having a good time?” George asks.

“Yes,” I say. I look down at my hands. “You?”

“It’s a nice event,” George says, or something bland like that. Nick raised him right, so George understands that banal exchanges are the social glue that hold our lives together.

He asks some question about why I’m here or what I do or where I’m from. He’s polite like that, and the line for the cash bar is long, even with George Clooney standing next to me. It doesn’t really matter exactly what he asks. The point is that I tell him that I’m from Kentucky, too. Like him. I grew up in a small town. My small town is by the Cincinnati airport, and I won’t have to explain to him that the Cincinnati airport is in Kentucky. He already knows that.

“My aunt and uncle taught in Augusta,” I’ll say eventually. “He was the baseball coach.”

“Oh, what’s his name?” George will ask. His eyebrows will go up and he’ll have that little smile that’s always there. Even when he’s frowning, it’s like he can’t quite make the ghost of the smile disappear.

Maybe he’ll know them and maybe he won’t. That’s not really what matters.

“Do you ever miss living in a small town?” I’ll ask him. This is the important question. This is where the whole conversation has been going. This is the point of meeting George Clooney.

The company my dad worked for had a factory in Augusta. For ten years, my Dad made that long commute from one small town to another. Sometimes we would go up with him for the annual picnic and to see my aunt and uncle.

In Augusta, there’s a church that sits right up on the main street, like a spectator who doesn’t want to miss a thing. My aunt and uncle’s house was old and had so many rooms I was convinced it must be magical. They had a garden around the corner. We walked down to it and waved at their neighbors who drove by as my aunt pointed out where a turtle took bites out of the low-hanging tomatoes.

There was nothing exotic about Augusta, even though it seemed to take so long to get there in the car. I would fall asleep with my head against the window in the summer on the drive, and I’m convinced the lightning bugs have never been as thick as they were then, streaking by as we sped along.

“Do you ever miss Augusta?” I will ask him.

I don’t know how George Clooney will answer. Whether he’ll say yes or no. Will he take a moment to think about it? Will he get a faraway look as he remembers? Or will those dark eyes close with a quick, low chuckle. “No,” maybe he’ll say. “Not at all.”

And then there will be nothing else for us to talk about.

Enjoyed both your texts today. Warm belly vibes.

The electoral college came out of not only racist but sexist and classist times in the 18th century- it was meant to keep the "rabble" in line more than anything else. Consequently, because of this, the college has interfered in many elections because it has political authority over and above a popular vote alone- the results of many of which would have been significantly different had it only been based on a popular vote.