What I learned in a novel workshop with Elizabeth Strout

Or at least the bits I can tell you...what happens in workshop stays in workshop

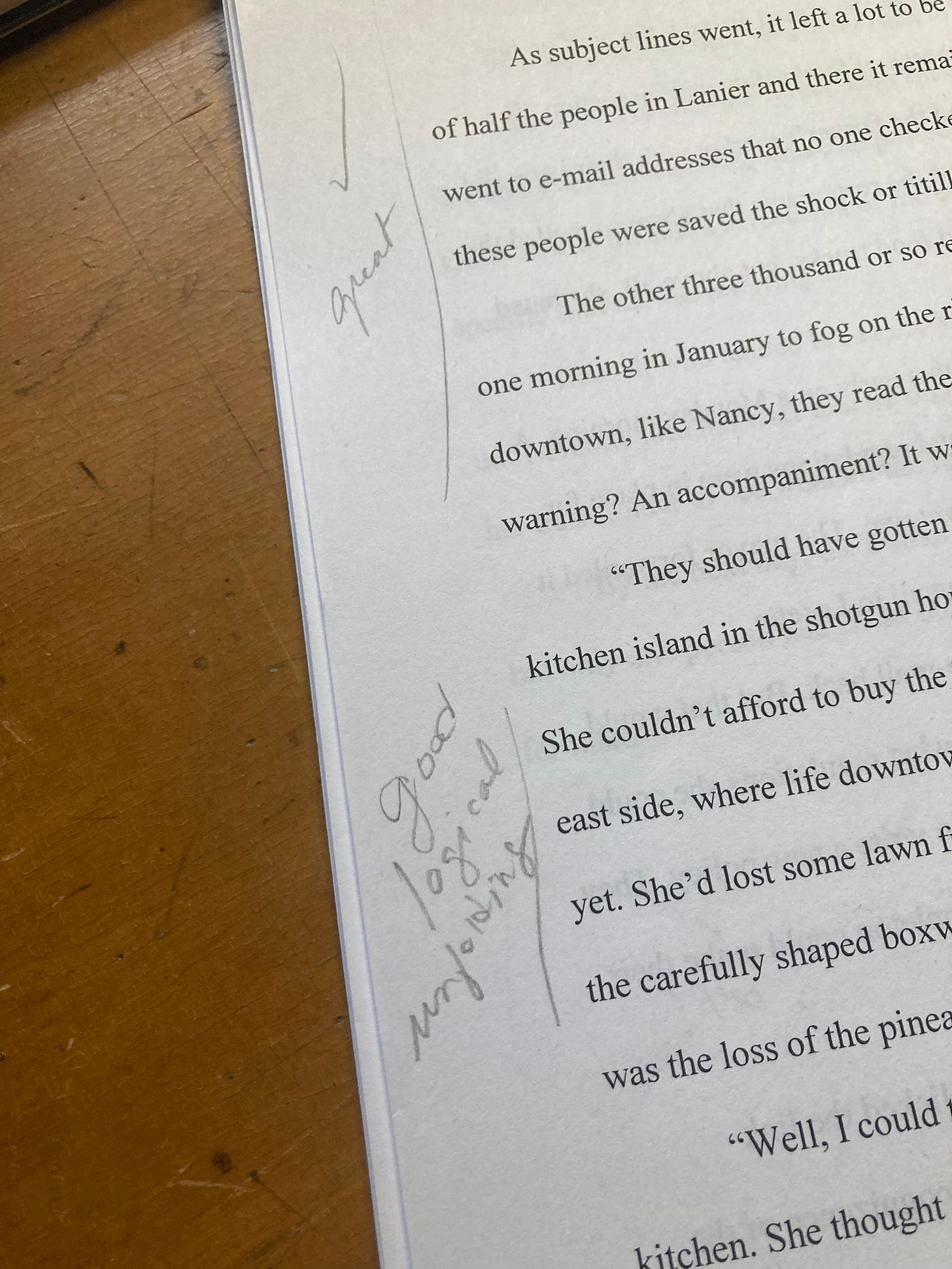

Still sort of giddy about even typing those words—"a novel workshop with Elizabeth Strout.” Yes, that was me. I took copious notes, because, of course I did. I can’t give everything away, but here are a few precious nuggets of writer wisdom, straight from the words of Pulitzer-prize winner and author of one of the best novels ever written—Olive Kitteridge—Elizabeth Strout.

- You must approach the page with authority. She spoke about this a lot, in her craft talk and in workshop. Where does authority come from as a writer? You have to believe that you are the only person in the world who can tell this story. You must believe this. If you don’t believe it, it’s not your story.

- Authority as a writer is essential because it makes the reader feel safe. Your job as a writer is to take the reader by the hand and lead them through your story. They’ll know that you might hit some rough patches. There might be mountains to climb and valleys to cross. It can be a difficult journey, but they have to trust that you’ll get them through in the end. Your reader has to accept you fully with a sense of safety and trust.

- How do you lose authority as a writer? Oh, there are so many ways, friends. You can lose authority by writing a false sentence. Pay careful attention to each and every word.

You lose authority when you show off as a writer. You will know when you’re showing off. Or if you don’t know, you’ll learn.

You lose authority when you write conventional text (words like smile, grin, chuckle, glower, glare…). Conventional text is the cousin to cliché. You must “render the object accurately in your own voice.”

You lose authority when your writing unwinds in jolts and starts. Every sentence should follow the sentence above. Practice chaining to avoid this, where you repeat one word in a sentence above and below.

Finally, you lose authority with what Strout called ‘twigs.’ A twig is any single sentence that doesn’t really need to be there. When you’re so lost in the text of your novel that you can no longer tell what are twigs and what aren’t, she suggests leaving your manuscript in random places around the house and sneaking up on it, so to speak. Take a glance at a page when you’re grabbing your morning cuppa or as you’re putting on your shoes. Trick yourself into seeing your words like a reader would.

- Don’t worry about plot. Literally, Strout said, “I probably would not worry about plot. First off, listen to the word…plot. It’s a horrible word.” Write what feels true. Write scenes that have a heartbeat and plot will emerge. I know, that’s a hard one, isn’t it? Pantsers all the way.

- Okay, if it makes you feel better, pick a scene you’re writing toward. In her first novel, Amy and Isabelle, Strout knew that Amy would get all her hair cut off. She had to earn that scene somehow. In Olive Kitteridge, the last story was the first she wrote. The rest of the stories were getting to that final scene.

- “[Writing] is all despair most of the time.” Preach it, Liz.

- But, also, you have to be curious. You have to have a natural sense of curiosity. “I’ve always wanted to know what it feels like to be another person,” she said. But we can’t do that. Ever. Writing and reading are as close as we ever come. Also true.

Up next, what I learned in the craft talk with Luis Alberto Urrea, who was also at Writers in Paradise, and is awesome and charming and so, so funny!