I’m reading Van Gogh: The Life after a visit to the Van Gogh museum in Amsterdam and much like Vincent at many stages of his erratic life, I’m a little obsessed. I have A LOT to say. So this may be the first part in a series. Stay tuned.

Also, this post may cut off in your email because of all the pictures, so read the full version online.

I love art museums, but they can also be exhausting. They’re exhausting when you have arthritic knees that make standing for long periods of time difficult. They’re exhausting when elevators are scarce and you have to go up multiple flights of stairs with those arthritic knees. They’re especially exhausting when they’re crowded, which the Van Gogh museum was, full of fellow tourists and school groups, the teenagers rushing from one painting to the next, snapping photos with their phones but never really looking.

So, no doubt, there was a lot I missed at the Van Gogh museum when I was there this month. Still, at one point as I was trudging through a crowded gallery, my husband came up to me, excitement in his eyes.

“Have you seen the sketches?” he asked. “They remind me of the ones you draw in your little book.”

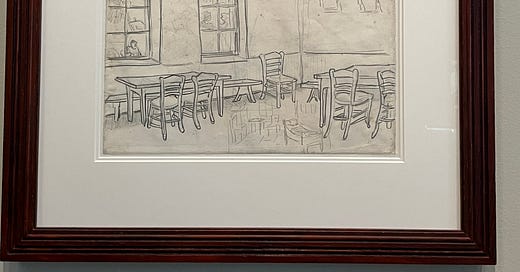

“Oh, where?” I asked and followed him to a series of sketches along one wall that was, blessedly, much less crowded than in front of The Potato Eaters or the sunflower paintings.

Van Gogh’s sketches, the exhibit explained, could be displayed only rarely and for short periods of time. The pencil and ink and chalk was too delicate. Too sensitive to light. Maybe this is why I have no memory of ever having seen a sketch by Van Gogh. I could only ever remember seeing the paintings, bold and assertive. If you could paint with color like that, why would you ever bother with pen and ink (this is a whole story in and of itself, about our reluctance to embrace the kind of artist we are)?

But here were tiny sketches in black and white. Yes, several were as small as the sketches I make sometimes in the little notebook that I carry in my purse. In one sketch in pencil and ink of the interior of a room Van Gogh was practicing perspective, the placard informed me. Van Gogh struggled with perspective (more on that later). In a tiny inset, there was a sketch of what would become The Bedroom.

I stared at the sketches for as long as my knees could stand it. Then my husband and I went down to the café to have a drink and rest. Next to us, a young Japanese woman was sitting across from a Japanese man as he played with yarn and Lego blocks. An art lesson? I have no idea. Some mysteries of the Van Gogh museum are destined to be unsolved.

I couldn’t stop thinking about those sketches, though. One of them hinted at Van Gogh’s future style, full of weird wavy lines and dots. But the one with the chairs wasn’t really any different than something I might draw. That fact was a revelation.

Van Gogh, one of the most amazing artists of all time, had drawn a sketch not much different from what I might draw. And he drew this sketch not when he was six or ten or even eighteen. Van Gogh drew that interior room when he was in his thirties. While he was in Arles. Van Gogh did not become serious about art until he was twenty-seven. And, at first, he really sucked at it.

The sucking part I wouldn’t learn until later, when I came home and started reading Van Gogh: The Life. The museum displays hinted at it, though. I knew that Van Gogh died in 1890. I began to notice that all the paintings were from after 1885, though, really, after 1887. That meant that the bulk of Van Gogh’s paintings were done in roughly three years. Could that be right? And that as recently as 1885, he still wasn’t that great as an artist?

I mean, this is Vincent Van Gogh, whose paintings are an industry unto themselves. They are some of the most recognizable images in the world. He had his own immersive tour. Vincent Van Gogh, whose painting of that famous bedroom hung in my college apartment, so that I feel at times as if I, too, lived in that room. Probably a lot of us feel that way. Like we have been to those places Van Gogh painted. Like we could take up residence inside those sunflowers.

Could that Vincent Van Gogh have been only mediocre when he was in his thirties, given that he would die when he was only thirty-seven? Was that even possible? Shouldn’t one of the world’s most “talented” painters have shown some sign of what was to come well before, you know, his thirties?

Over and over again in the book, Van Gogh: The Life, people repeat the same general truism—“Artists are born great.” Talent is inherited. Biological. You either have it or you don’t. Period. End of story.

This is a familiar narrative. Picasso began his formal art training at the age of seven. Mozart began to compose at five. Chopin was giving public concerts and composing by seven. Even if artists aren’t child prodigies, they show some sign of their future greatness. Their hidden talent breaks through in glimmers of precociousness. At least in the established narrative, there’s always someone who knows. There’s always some prophet who looks at young Prince or Miles Davis or Georgia O’Keefe and foretells their greatness.

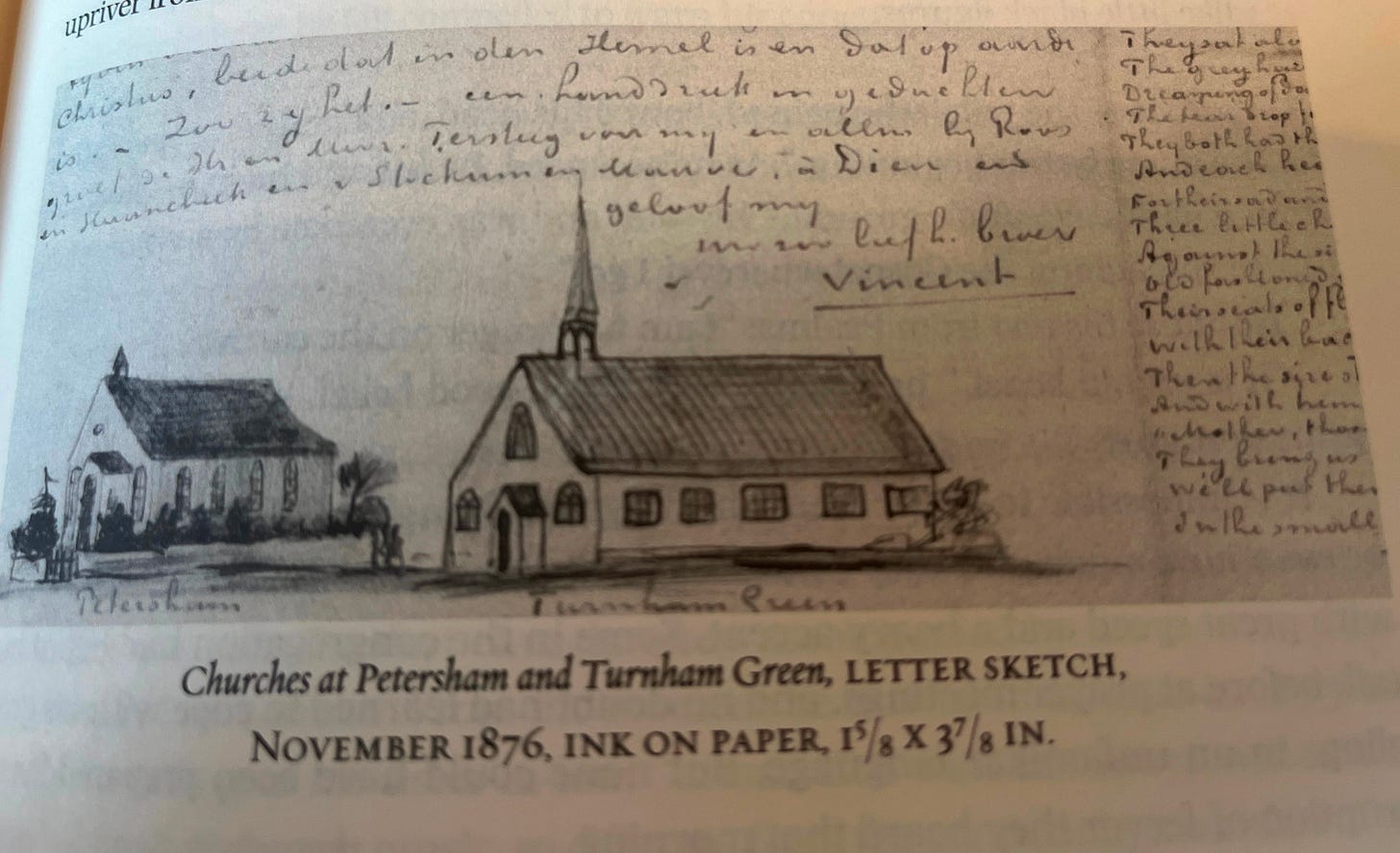

As far as I can tell, all anyone knew about Van Gogh as a child was that he was super annoying. A perpetual disappointment to his parents, as well as his rich and successful uncles. He was angry and prone to tantrums. He made a few sketches because everyone in Van Gogh’s family drew. They were artsy that way.

But no one thought Vincent was any better at these little drawings than anyone else. There’s a moment in Van Gogh’s twenties, when it appears that it will be his brother, Theo, who will become the artist. Even at that moment, it doesn’t seem to occur to Vincent or anyone else that he might be the artist in the family. It’s only after Vincent fails miserably at a whole host of attempted jobs and obsessions that he turns to art.

That happens when he’s twenty-seven. He decides he wants to be an artist (instead of a preacher or missionary). Even then, no one in Van Gogh’s life says, “Oh, yes, well, of course Vincent was destined to be an artist because he’s so talented.” Mostly what they say to each other (and Vincent) is some version of, “Shit, this doesn’t seem likely to turn out any better than that whole missionary thing.”

If there is anything that seems to be true about Van Gogh it’s that he had a pronounced tendency toward obsession. For most of his life, that obsession was turned toward God (and his father, though those two are sort of hard to separate for Vincent). When he decides to become an artist, he turns all that obsession towards mastering art. His first step? He buys the 19th century equivalent of Learn to Draw in Ten Easy Steps. I kid you not. He buys books and begins to practice the exercises. And the results are…not good.

But he keeps at it. He keeps drawing. He keeps sketching. He goes through paper and pencils and ink at a rate that alarms his brother, Theo, who is footing the entire bill for this enterprise. At various points he tries, briefly, to actually attend an art academy. To, you know, take lessons. It never works out because Vincent does not play well with others.

He understands that he needs to learn from other artists. He wants to watch other people paint. He wants a mentor. He wants to be part of a studio. But something about him will not allow him to tolerate other people (or for them to tolerate him) long enough for this to happen.

But Van Gogh keeps working in his relative isolation. He works and works at it. “The more one makes, the more one wants to make,” he writes to Theo. He produces shitty drawing after shitty drawing. He sends them off to his brother and his uncles and anyone else he can think of. No one thinks they’re any good.

He tries watercolor and chalk and pastels. He talks about wrestling with these new materials. He’s not good with any of them. In one brief moment, he finally gives oil paint a try and the results are amazing. But out of some perverse aversion to actual success (more on this later, too), Van Gogh abandons oils after that initial success.

Van Gogh doesn’t paint The Potato Eaters, which he considers his greatest masterpiece at the time, until he’s thirty-two, which is five years after he decided he was going to be an artist. He doesn’t paint the first sunflower study until 1888, seven years after he decided he was going to be an artist. In the time in between, what he produces is mostly, well, crap.

Even after he starts producing some of the paintings he will be famous for, it’s not clear how good he is at things like, you know, perspective (still). Or how good he is at faces and hands. Van Gogh for most of his very brief career as an artist wants to be a portrait painter. What holds him back is that he sucks at painting people.

Do the people in The Potato Eaters look so grotesque because Van Gogh wanted them to look that way or because he couldn’t paint a realistic face? It’s sort of unclear. Even when he shacks up with Paul Gauguin in Arles, he’s demoralized by Gauguin’s ability to paint figures from memory, without a model. Gauguin can make things up and then paint them. Van Gogh cannot.

For me, there is no doubt that Vincent Van Gogh is one of the most amazing artists to have ever lived. This is true even though his images have become so ubiquitous. I suppose some people can look at The Starry Night and be unmoved. Certainly, his contemporaries didn’t feel much when they looked at it, I guess. But to look at most Van Gogh’s paintings is to find yourself in an intimate conversation with some great passion. Van Gogh didn’t need to be able to master perspective or faces and hands in order to be able to do that.

Is that talent? Or something else? What is talent, anyway? The older I get, the less convinced I am that such a thing as talent exists in the way we normally think of it. I don’t think you have to be born a great artist. I think you can become one. I think that’s what Vincent Van Gogh did.

Van Gogh sucked as a draughtsman for a long time, but when he used oils for the first time, it was a revelation. Was that talent or was it the result of all the hard work he’d done in other mediums for so long, working its way out on a subconscious level so that oil painting felt effortless?

There was also clearly something inside Van Gogh that was burning to get out. When he found the right subjects and the right medium and the right moment after the right amount of effort, it erupted out of him to glorious effect. Is that what talent is? Not a biological inheritance, but a confluence of circumstances and hard work and luck that is too complex to ever quantify? If Van Gogh had decided, instead, that he wanted to be a poet or a novelist (which in some ways, seems more likely given how prolifically he wrote), would it have had the same result? Or did it always have to be oil paint?

I don’t know what the answer is. I don’t know if there is such a thing as talent and if there is, I don’t know whether Vincent Van Gogh had it or not.

What I do know is that for the rest of my life, when I think of Van Gogh, I’ll certainly think of those iconic images. The sunflowers. The irises. The bedroom. The wheat fields. The starry nights. I’ll think, yes, of the ear. It’s hard not to.

But I’ll also think of a twenty-seven year old furiously working his way through the 19th-century equivalent of YouTube videos on how to draw. I’ll think of that moment and his decision and then the work he put in to make that decision real, even though no one around him believed he had even the slightest hope of ever succeeding.

I’ll think about those little sketches in the Van Gogh museum. I’ll wonder how many of us might be Van Gogh’s in waiting, lacking just the right amount of hard work and luck. I’ll imagine the amazing things all of us might have hidden inside of us, waiting to be released.

Copy edits for Sex of the Midwest are done! Hurray! Read some about that process at the and at the link below! Now on to cover design and proofreading.

One of the things that emerged from the copy editing process was a cast of characters at the back of the book. Henriette had this idea originally, borrowed from Tom Drury’s novel, The End of Vandalism. But I couldn’t figure out how to make it work until I saw the copy editors list of characters, which included funny ones like, “Joshua, waiter, cranky, dances.” So now there’s a cast of characters which I might be sharing this summer before the book releases.

Welcome new subscribers and thanks for being here and for subscribing if you have and for considering hitting that subscribe button if you haven’t already!

I did find this fascinating! Hopefully very encouraging for other artists of any sort. It reminded me that my mother painted in oils as a hobby all her life, and while they were competent, I never felt they were truly inspired or beautiful. Then, in the last years of her life (she died in her late sixties) she shifted to water colors, and I have two still lifes that I found delicate and lovely. While I never had the goal of becoming a great writer, I have been happy to have become a writer of light fiction that people enjoy, and that success didn't come to me until my sixties. Just glad I didn't die before 40, because....well, for lots of reasons...but also because it would be sad not to have experience the satisfaction of fulfilling a dream I'd had since I was 12.

I have looked at many Van Goghs over the years and entered into his world. He had a vision. Executing his vision was not about draughtsmanship. You make an excellent point about the astonishingly short time in which he produced his great work—the paintings that expressed his unique and unforgettable vision. Without incredible tenacity, he couldn’t have done it. But hard work alone won’t make an artist in any medium. I have seen people work hard to become writers and never produce any memorable writing. So I’m a believer in talent, although vision will do as well.