For all the people still stuck on the crappy court

Gender, athletic performance and why I wrote my young adult novel, FAIR GAME

There’s always a crappy court. And more often than not, the girls are on it.

As someone who’s been teaching about gender for over twenty years, I should have known this. Maybe I did know it. Maybe part of me thought it was something that happened often in the past, but not in the 21st century.

I don’t remember which class I was teaching, but I know we were discussing gender inequality. I like talking about sports, so that’s a topic that comes up a lot. I wish I could remember which student told me the story of the women’s team always having to practice on the crappy court. I can remember how pissed off she was about it. Her team was good. They had a better record than the boys, but it didn’t matter. The boys got the ‘good’ court. The ‘main court.’ The girls got whatever was left over.

From that story followed more over the years. We talked about why homecoming in high schools and colleges always centers on football, a male-dominated sport, even when the football team is horrible. We talked about the way a college golf coach who was supposed to be coaching both the women’s and men’s teams ignored the women for most of the season. We lamented the condescension of team names like the Lady Cougars or the Majorettes.

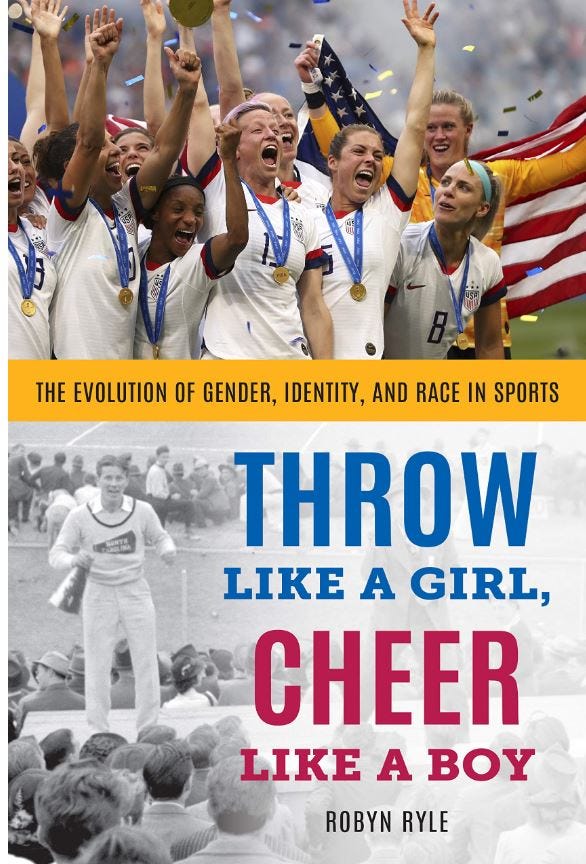

I stored these stories away in my back of my mind until 2019, when I wrote the book proposal that would become, Throw Like a Girl, Cheer Like a Boy. The idea was a book for kids that snuck a lot of sociology into fun stories about sports. I knew a lot at that point about how flawed a lot of our assumptions are about biological gender differences. I was well-acquainted with all the bullshit arguments for why trans girls and trans women shouldn’t be able to play sports as their actual gender.1

In the outline of that proposal, I included a chapter on gender differences in athletic ability. I had no idea what I’d put in the chapter, but I thought it would be interesting. It’s always felt like a received truth that of course men are better athletes than women. Of course men are faster and stronger. But I’d been reading and learning about gender long enough at that point to have an inkling that maybe that wasn’t actually the case. I knew for certain that both gender and biological sex were made-up things. That had to matter for sports performance and gender, right?

What I found as I did the research for that chapter was surprising. Between 1922 and 1984, women reduced the performance gap in many elite sports from 30 percent to 10.7 percent. Many people assumed the gap would close altogether, but since the 70s, the gap has shown little sign of movement.

This doesn’t mean that some women aren’t faster or stronger than some men. All gender differences are statistical rather than categorical, which means there’s a lot of overlap. Think of height. Yes, the tallest man in the world is a man, but that doesn’t mean all men are taller than all women. Whatever gender difference you pick, there’s always overlap because men and women, despite the popular books, are not species from different planets.

Still, that the gender gap in athletic performance hasn’t moved seems to indicate that there’s a real biological limit on women’s athletic ability, a barrier that can’t be crossed. Is that actually the true? The more research I did about gender and athletic ability, the more I began to suspect that the real answer to the question of whether men are better at sports than women is, we just don’t know…yet.

There are suggestions that physiologically women could have an advantage in some sports, especially those involving endurance.2 Women are better, for example, at long-distance swimming. Like, swimming across the English channel. Women’s endurance plus higher body fat keep them buoyant and warm in cold waters, which are distinct advantages. Also in events like the Iditarod, which also involves cold and endurance.

Of course, long-distance swimming and dog sledding are not quite as popular as football, soccer or basketball.3 Some sports scholars have asked, is that truly a coincidence? Could it be that our most popular sports are also the sports that most highlight the gender differences in athletic ability for a reason? Do we like the sports that clearly demonstrate men’s supposed superiority precisely because they affirm our deeply held beliefs about women’s inferiority? I think we have to consider this at least a strong possibility.

The real reason I think we don’t know for sure about the possibility of women’s athletic abilities is that we’re not even close to reaching full equality in regards to women’s and men’s sports. Yes, things have gotten much better in the fifty years since the passage of Title IX in the United States. But the differences in men and women’s relationships to their bodies go so deep that it will take much more than fifty years to reach an even playing field.

Take the example of skirts. In the U.S., girls wear them and, by and large, little boys do not. In theory, skirts should make movement much easier for girls than boys. Skirts are less restricting, after all. But research tells us that girls as young as three years old have already learned that they must be more careful about how they move in a skirt. If their skirt lifts, boys will see their underwear and they understand that this is a very bad thing. Hence, at three years old, girls begin to move in more restricted ways than boys do. Add to that the extra patrolling of their movements by teachers and other adults which girls are subject to and we can see that starting at age three, girls begin to gain less experience freely moving in their bodies than do boys. How does that affect their eventual athletic ability? We can’t know until we stop patrolling girls’ movement.

The biggest elephant in the room when it comes go gender differences in athletic performance has to be the inequity of reward. At all levels, girls and women get less in return for being great at sports. Girls drop out of sports at much larger numbers than boys, especially around the age when they hit puberty. This is the same age at which it becomes much less acceptable for girls to be tomboys. But also, when girls’ bodies develop, their relationships to their bodies changes in heartbreaking ways. The world tells them their bodies will put them in danger from men and pregnancy. They go from acting in their bodies to having their bodies acted upon.4

Add to that the fact that in almost every sport a girl plays, she knows she will never make as much as her male equivalent, assuming she even has the possibility of making any money at all. Tennis and soccer are the only two sports in which women come close to making the same amount of money as men and the battle for that equality has been long and hard-fought.

If you’re a regular watcher of sports like the NFL, you’re well familiar with the upward mobility narrative of poor (mostly BIPOC) boys clawing their way out of poverty by making it to the NFL. These narratives suggest that buying their parents a new house is a big motivating factor in their athletic success. They worked hard at their sport in order to achieve that financial success Very few girls, whatever their economic circumstances, will ever be able to buy their parents a house with the earnings from their sports career.

Nor will they make a mint in endorsement money. Or will they be able to have a cushy career in sports broadcasting. Even if they want to coach other women in their retirement, they’ll still have to compete with men for those jobs. They’re not likely to be asked to join the front office or become general manager.5 The amazing athletic performances that women do currently achieve are all in the face of the knowledge that at no stage will they ever be compensated for them as they would if they were a man.

All of this is to say that in a very different sort of world, maybe women could be just as good at men on the field and the court. That’s what I believe and when, in my classes, I lay out all these arguments and suggest this possibility, I see a light go on inside the eyes of my women students. I feel an energy pass through the room. I sense a burden that the women didn’t even know they were carrying being lifted. Maybe, just maybe, they are just as good, I can seem them thinking. Maybe that world is also possible.

That’s why I wrote FAIR GAME—to bring that moment of possibility to as many people as possible. It’s the story of three young women who find themselves stuck once again on the crappy court and what happens when they decide to do something about it. I wrote it to see young women’s eyes light up and that burden lift. To open up that perspective especially for all the women and girls out there who have had to play on the crappy court. But for everyone else, too. If it’s not the girls on the crappy court, it’s the poor kids. Or the dark-skinned kids. The kids who aren’t able-bodied.

Someone always gets the crappy court. But what if it didn’t have to be that way? FAIR GAME is my wish for what could be, sent out into the world.

FAIR GAME is out in the world tomorrow. Pre-order it here or here or go to your favorite local indie bookstore and ask them if they have a copy or can order one for you.

I’d love to hear your own stories about being stuck on the crappy court. Or having to play with the old equipment. Or having a coach who wasn’t really interested in helping your team. There are so many stories like those of Sedona Prince, whose 2021 TikTok showed the differences between the weight facilities for the women’s NCAA tournament and the men’s (spoiler alert—the men had a whole room and the women had a single rack of weights).

If you liked this post and found it interesting, please do share it widely. I’ve pitched an essay on this topic nine times now to big media outlets with no response, I think because even the possibility that male dominance in sports might not be true seems too outlandish or unthinkable. But nothing is unthinkable and usually that means the horrible things, but let’s spread the idea that great and wonderful things are also thinkable, yeah?

There’s a whole chapter on this in Throw Like a Girl, Cheer Like a Boy, and I’ll be writing more about it later, as there’s a nonbinary character in FAIR GAME who is also a high school wrestler. Their experiences showcase how gender segregation in sports—one of the last places in our society where we see this as acceptable—makes the participation of nonbinary and agender and gender fluid people difficult to impossible.

This will not be surprising to anyone out there who identifies as a woman. What does it mean to be a woman, of any sort, trans or cis or femme, except to be a person who endures a lifetime of shit?

You might notice that I left baseball off that list and ask yourself why. I’m not convinced that women couldn’t, right now, play professional baseball. If you are a baseball fan, you may have noticed that baseball has no body type, at any position. Elly De La Cruz (the fastest man in baseball) is 6’5”, rangy and thin. His buddy who proceeded him to the Bigs, Matt McClain, is 5’11” and, well, not at all rangy. Some pitchers are big guys (Pablo Sandoval, aka, Kung Fu Panda). Some pitchers are tall and skinny (Randy Johnson, aka, Big Unit, who once killed a bird with a pitch). This is true almost all across the field. I definitely believe a woman could pitch in the MLB and, in fact, women have in the minors and professionally in Japan. Great story along those lines, Jackie Mitchell, a seventeen-year-old woman, struck out Babe Ruth and Lou Gehrig in 1931. Within weeks, the baseball commissioner at the time, Kennesaw Mountain Landis, had banned women from baseball.

You can also add to this the embarrassment and discomfort that many girls face after puberty from inadequate sports bras and the looming horror of bleeding through a uniform when you’re menstruating. Students in my class told a story about having to explain to their (of course) male coach that they would rather not have white pants as their uniform because every single spot would show.

This is changing some and very slowly. Check out the Racial and Gender Report Card if you want to know more on a sport by sport basis.

Wow thanks for this! So fascinating and I want to read both your books. I’m currently writing a 9-12 fiction book about a girl’s football team as I was trying to find a book for my niece’s birthday and there simply wasn’t anything of the sort!

I remember being at a Bristol city womens game (UK football) last year and behind me weee these blokes who must have been season ticket holders for the men’s team. They were constantly saying things like “wow they’re actually pretty good!” And then eventually decided that their Sunday league amateur team of 30-50 something men would still beat them “because of the physicality” 🙄🤦🏻♀️

Just fyi: received an Amazon message stating my copy of Fair Game was delayed and I had to approve the shipment and delay. Hope this means you're selling out but fear it's a discourager for buyers.