I loved sociology before I even knew what sociology was. That’s how hardcore I am. I believe it’s totally possible to think sociologically without having ever had an actual sociology class (I see you, Glennon Doyle). In high school when I was trying to figure out the rules for how popularity worked as a social system, I was thinking sociologically.

Still, I see how to other people, being a sociologist can seem like, well, sort of a bummer. All the time talking and reading and writing about inequality. All the time revealing how much more fucked up the world is than you thought it was. It can be a lot.

The other day, a friend and I were talking about gender inequality or something along those lines. I was probably pontificating a bit. At a party once, I was reeling off some random fact and a woman looked at me across the table and said, “You know things.” It didn’t sound like a compliment, but the fact is, I do know things. I know a lot of things that I keep to myself most of the time, but if you ask me about them and you seem genuinely interested, I’m more than happy to tell you.

“How do you keep from getting down?” my friend asked somewhere mid-pontification.

Or, “Do you have hope for the future?” which is the version one of my students will ask me from time to time.

I will confess that I have less hope in 2023 than I did in, say, 2016. But I still do have hope, even with knowing the things. In fact, the knowing things is part of what gives me hope.

I am a curious person and that means knowing things gives me great joy. Or it might be more accurate to say that not knowing things gives me great joy because then I get to try to figure it all out. For example, in response to my CNN Opinion piece from last week, a very thoughtful person e-mailed me asking about his daughter’s sports experiences. He found that when his daughter played on co-ed teams there was a lot more competitiveness than when she played on a girls-only team. He wondered if there was research about this.

I’m still looking around for the research (if anyone knows of any, please pass it along), but his e-mail raised so many questions. Is there a self-selection process where parents who encourage more competitiveness in their daughters are more likely to allow them to play co-ed sports? Do girls-only teams absorb cultural ideas about feminine fragility and unconsciously discourage competitiveness in a way co-ed teams do not?

If you look up the rules for early women’s basketball, you’ll find that there was no dribbling or guarding or really much running allowed. Any of these strenuous and aggressive activities were thought of as inappropriate for women. They also believed that competition might shrink women’s uteruses and render them infertile (not making that up). It makes sense that these ideas about competition and femininity not mixing are still around, in less extreme forms.

I like knowing things and I like asking questions even (or maybe especially) those I don’t have the answer to. But also, I can’t do anything about all those inequalities and injustices until I know things. If we want to make women’s sport more competitive and aggressive, we need to first understand what’s going on.1

If I want to understand how we got to this current moment in our country’s history, I have to understand what’s really going on. Sociology helps me see that the narrative of poor, mostly rural people voting for Trump because they’re too stupid to know any better isn’t the truth. First, 55% of voters with a household income under $50,000 voted for Biden while 54% of those with incomes over $100,000 voted for Trump. In other words, the majority of rich people voted for Trump while the majority of poorer people voted for Biden. One study found that it was precisely poor people who helped defeat Trump in 2020.2

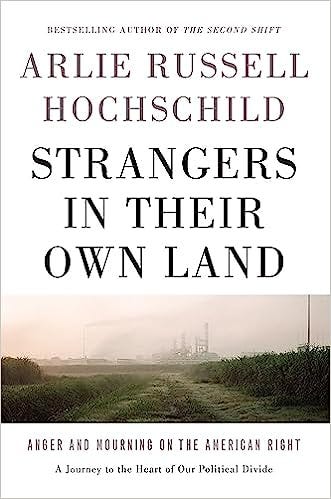

Sociology also helps me understand that there are real problems with a narrative that sees some people (Democrats and liberals) as rational people who vote on the basis of logic and reason and others as mindless idiots whose voting patterns are simply incomprehensible. Sociologist Arlie Russell Hoschild, pioneer in the sociology of emotions, found well ahead of the Trump election that, not surprisingly, people don’t vote rationally. They vote emotionally in ways that line up with the narratives they’ve constructed to help them understand the world. This isn’t just true of Trump voters. We all use emotions much than rationality to make decisions about who to vote for because that’s how we make most of our decisions.

The narrative that we smart, enlightened people vote on the basis of rationality while everyone else is just an idiot is so seductive. Sociology helps me understand that, too. That narrative is ready-made for an us vs. them dynamic. We are smart. They are stupid. It’s so, so satisfying to believe that but, and here’s sociology’s bottom line, the truth is always much more complicated.3

Knowing things gives me hope because knowledge is always a first step. It’s a necessary first step, I would argue. As a professor, I get to spread that knowledge. I get to plant it like seeds inside the brains of my students, just exactly as sinister as all those fuckers trying to control what happens in classrooms would like to believe. Yes, that is exactly what I’m doing. Giving students the knowledge they need to change the world and make it better. If you’re afraid of my ideas, go get your own Ph.D. and do my job. I’ll take you on in an academic cage match any day.

Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. (also a sociology major) famously said that the arc of the moral universe is long, but it bends toward justice. How did he know that? He didn’t. He decided to believe it. He had faith. What’s the alternative? Despair—the certainty that today will be exactly like yesterday. Despair cannot fuel a social movement, but hope can.

But also, Dr. King had sociology at his back. The man had knowledge and I like to believe that’s at least part of what gave him the hope necessary to lead a movement. He understood that societies are always in the process of change. Sometimes it’s slow. Sometimes it’s fast. But if you understand what’s going on, you’ve got some hope of nudging that change toward justice. At least that’s what I choose to believe.

This weekend I went to an actual bookstore and saw a copy of FAIR GAME, my young adult novel, on the shelves and that was pretty awesome. It was at the Carmichael’s on Bardstown Road, so Louisville folks, check it out.

If you missed my CNN piece about gender and athletic performance, read it here. I’m still getting a lot of very helpful explanations as to why I’m wrong, but also lovely e-mails like the one I talked about above.

Indianapolis book event details still forthcoming, but don’t forget all these events coming up soon!

Tuesday, August 15, 5:30 - 6:15, Madison Public Library. Girls vs. Boys: Exploring Gender and Athletic Performance. Follow-up reception and book signing at Red Roaster.

Monday, August 21, 7:00, Joseph-Beth Booksellers-Rookwood. Cincinnati.

Saturday, September 16, Village Lights Bookstore (more details to come).

Saturday, October 21, Kentucky Book Festival, Joseph-Beth Booksellers-Lexington.

This is a pretty big ‘if.’ Does gender equality in sports look like women being as competitive and aggressive as men or does it look like sports in general becoming less competitive and aggressive? There’s nothing that says games have to be so aggressive. There are lots of games where no one wins, even if we don’t much play them in the U.S. It’s not all difficult to trace the relationship between our capitalist values and competition in our sports. So maybe the better question is, what do we want our sports to look like?

Part of the reason this narrative is so powerful and captivating is that, first, it fits right with our deep-seated beliefs about poor people in the U.S.—that they’re stupid and deficient in some way instead of just victims of a system that is designed to create poor people…yeah, capitalism. But second, the narrative often uses the language of ‘the working class’ and our racism leads us to picture the working class as mostly white. It is not and never has been in the U.S. This is another reason I love sociology. It’s a tool for unpacking all these assumptions we carry around inside our heads.

If sociology had a slogan, that would be it—the truth is much more complicated. Or, “It’s socially constructed.” That’s why we don’t get on the talk shows. No one wants to hear someone explain how complicated it is. They want an over-simplified, both-sides, black and white sort of bullshit.

I was raised by two sociologists, and I can see that I was taught to think from this perspective from all those years of hearing them, and then joining them in sociological discussions of everything from why a particular aunt had trouble getting along with her mother-in-law, to why certain people in our church didn't get excited as my family did to join in the civil rights movement, or why a girl in my class who was very smart had been tracked into the non-college bound track to be trained as a secretary (and not surprisingly was the first to get pregnant,) while her brother, who wasn't as academically inclined and would have been very happy to get into automotive trades, was being pushed to take classes that he failed. Not surprisingly, when I got my doctorate in history in the 1970s, my field of study was "social history" my minor field sociology, and I taught women's, urban, and ethnic studies classes. And I agree, this sociological frame of mind, while it doesn't keep me from knowing how bad things are, it does keep me from despair, and it does keep me from the simple dichotomies of liberal good, conservative bad. My father, as he started down the slope into dementia, was very agitated by the shift to right-wing political successes in the late 1990s and early 2000s, and he spent a year taking down his old sociology texts from the 1950s tell me that what divided Democrats and Republicans, liberals and conservatives, was the fact that conservatives had high intolerance for ambiguity, while for liberals, had a high tolerance for ambiguity. The result was conservatives would believe anything they were told was THE TRUTH, but liberals would tend to see different sides of questions, believe the answers to problems weren't black or white, and that mades it more difficult to get a unified message out there. The dementia meant he didn't understand how a letter to the editor, or challenging his church's adherence to a literal interpretation of the bible wasn't going to change everything over night, but I must say, I still believe his analysis had a good deal of merit. So, do go on with your sociological world view, and I will certainly enjoy going on reading what you are writing!

Forever grateful for the seeds you've planted that have grown into a forest in my mind, it's liberating to finally have the lens to see and the words to describe those things I once thought were invisible forces <3