People are willing to give up a lot in order to make sure others don’t get more. That’s what experimental economist Daniel Zizzo found in a 2001 experiment. He gave some volunteers more money and some less. He found that volunteers were willing to spend their own money if it reduced the amount of money others had.

Zizzo called it burning other people’s money. A surprising number of people were willing to reduce their own wealth if it would also reduce the wealth of other people, a phenomenon that isn’t economically rational, but is explained psychologically by our sense of how “deserving” we believe others to be. The study helps us understand why specific policies to reduce inequality in the United States are often so unpopular—we tend to believe everyone is less deserving than ourselves.

It might also explain what’s happening with my Reds, where owner Bob Castellini was among four owners during the recent collective bargaining agreement negotiations to vote no on what at the time was the “best and final offer” from the players. With that ‘no’ vote, Castellini and the other owners showed they were more than willing to burn their own money in the form of lost games to prevent the “undeserving” players making significant gains from what is a $10.7 billion dollar business.

Once the players’ association and the league did reach an agreement—one that did not include many of the demands the player started with—Castellini showed just how he felt about the small gains players did achieve by commencing what in baseball we call a ‘fire sale,’ or in this case, petty revenge.

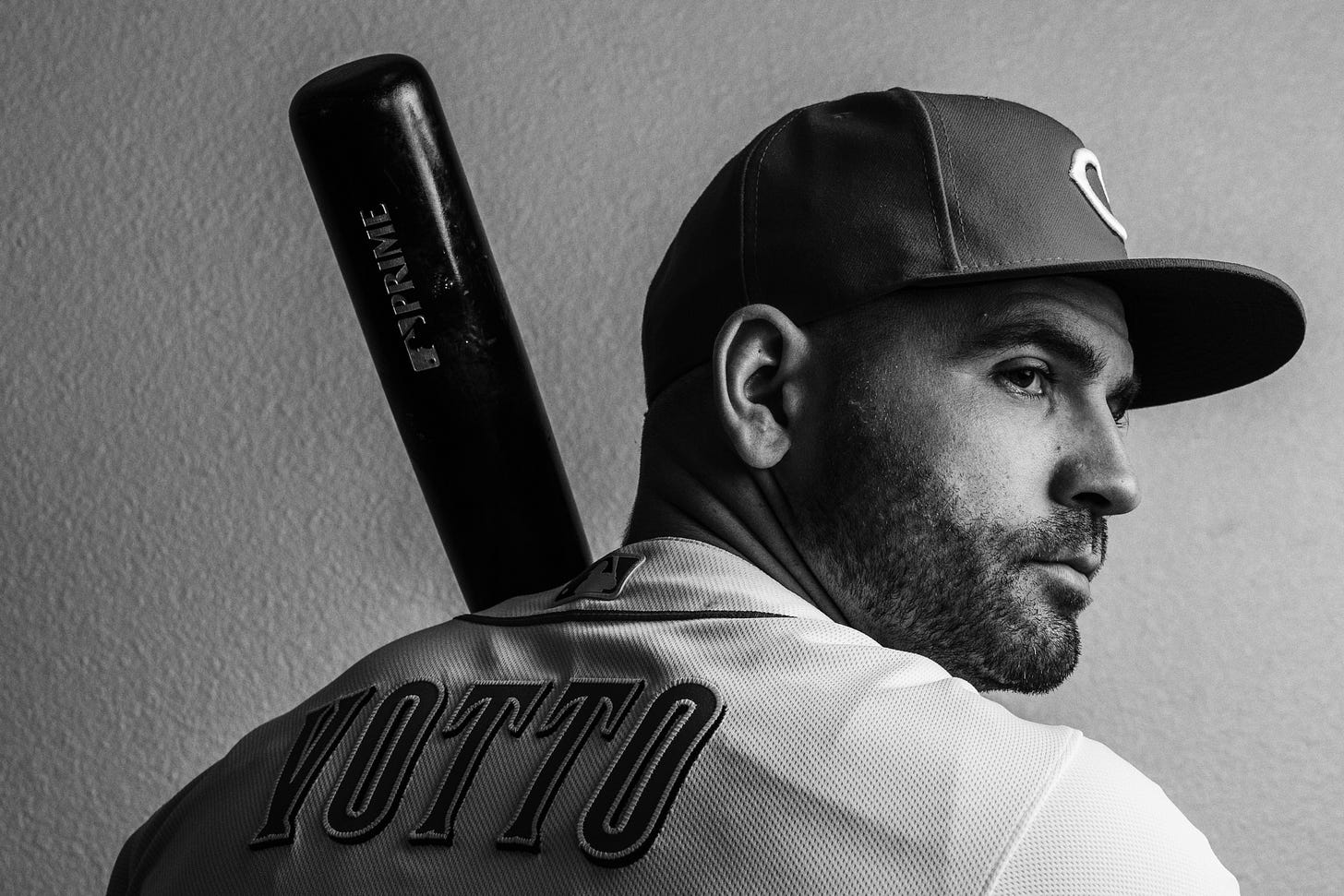

The Reds traded starting pitcher Sonny Gray. Then the charismatic third basemen Eugenio Suarez and All-Star outfielder Jess Winker. Next the fiery and outspoken relief pitcher Amir Garrett. Finally, Nick Castellanos departed for the Phillies, leaving aging first basemen Joey Votto as perhaps the loneliest man in baseball.

Why should you care about any of this if you’re not a Reds’ fan? Because baseball provides an interesting microcosm for inequality in society at large and a good refresher on exactly how capitalism works (SPOILER: Also, why capitalism sucks.)

The owners are, of course, the bourgeois. They own the means of production and they’re motivated by the desire to keep as much of the profit for themselves as possible. I know it sounds strange to call the players the proletariat, but by Marx’s definition, they are. They’re selling their labor in order to live.1 What the players association wants is a fairer share of the $1 billion in growth the league has experienced between 2015 and 2019, a period in which players’ salaries declined. In other words, they want an equitable distribution of profits, something more in line with the standard 50/50 split in other leagues like the NFL and the NBA.

The players aren’t arguing that they should make the same amount of money as the owners. They’re not socialists. They weren’t arguing for a radical overhaul of the status quo, even though that status quo is responsible for the currently skewed distribution. All they want is a slightly larger piece of a very big pie.

“But Mike Trout got a $426.5 million contract!” you might be yelling at me right now, which is true. It’s also exactly what the owners and the CEOs and the other capitalists want you to think.2 Sure, get mad at Mike Trout. Forget about the fact that Arte Moreno as an owner makes enough money to pay Mike Trough $426.5 million dollars along with the salary of the other 25 players on his team. To paraphrase Chris Rock, Mike Trout is rich. Arte Moreno is wealthy. There’ a big difference between the two. Either way, you need to ask yourself why you’re mad about Mike Trout or Patrick Mahomes or Steph Curry but not about the dudes (it’s always dudes) who pay them.

The players want a more even distribution of profits. This is something all of us should want. It’s not a radical idea. And yet, we live in a country where the average CEO earns 351 times what his average worker makes.

A slightly larger piece of the pie is what Americans in general say they want. Baseball is a microcosm of a central contradiction at the core of inequality in the U.S. Though the majority of Americans, across party lines, favor a more equitable distribution of income and wealth in the abstract—a distribution that resembles countries like Sweden— they’re unlikely to support the concrete changes that would get us there. The psychology of inequality—being willing to punish ourselves to prevent anyone else from benefitting—gets in the way.

Another psychological concept, upward comparison bias, might help explain this reluctance. We tend to compare ourselves to those who are doing better than us, rather than to those who are doing worse. Maybe MLB owners are looking at their even wealthier corporate counterparts and feeling deprived. Certainly, the owner of any given team isn’t making 351 times what his average player is. If Jeff Bezos can get away with it, why not Arte Moreno?

The players association, on the other hand, shows us what it might take to break this mental logjam in our thinking about inequality. Their union is famous for its culture of collective thinking. In addition to wanting a more equal distribution of revenue, the players other demand is to end ‘tanking,’ the practice of deliberately depressing payroll in a way that sacrifices a team’s ability to compete. They want to play in a league in which the people in charge actually want to win games, instead of just generating revenue—another radical concept. They want to make it less possible for owners to do what Bob Castellini is currently doing to the Reds, reducing salary and giving fans a team that is almost guaranteed to finish last in their division. Exciting, yeah?

Let me put if more plainly—the players want baseball to be good. The owners just want to make money. Period. End of story.

You’d think we’d have figured this out by now, but this is how capitalism works. The free market and competition are supposed to make for a better world if you believe Adam Smith.3 Yeah, how did that work out for us during the pandemic, when we realized our hospitals are built to the exact capacity to turn a profit with not one extra bed to spare? How is that working with our internet, which is about the worst quality in the world thanks to the beauty of the “free market”? How is capitalism working if you’re diabetic and your insulin costs $98 compared to about $7 in the U.K.? Should I go on? No, because it’s raising my blood pressure and I live in a capitalist society that ties my right to healthcare to my job and does a shit job of even that, so I really can’t afford the meds to fix it.

On and off the baseball diamond, inequality hurts the larger group. In the U.S., inequality hampers economic growth, drives up crime rates, and eventually, creates a population of consumers who can no longer afford to buy the products you’re making.4

Our complacency about inequality is hard to stomach as a baseball fan. It’s hard to stomach as a citizen of a country with a mindset that produces mind-boggling levels of inequality beyond the baseball diamond. On and off the field, we need a new way of thinking. Also, sell the team, Bob.

Hey, thanks for reading if you made it this far, even though it was about baseball. And Marx. Two of my favorite topics, really.

This post is brought to you by the owners, who when they did finally end the lockout (not a strike, don’t you dare call it a strike), made it impossible for a slightly different version of this newsletter to be published in The Washington Post. Yeah, for those of you keeping track, it’s March and I’ve already missed out on two shots to be in The Washington Post because of sports. You’d think I’d learn, wouldn’t you?

Seriously, if you like reading about sports and inequality, check out my book, Throw Like a Girl, Cheer Like a Boy. It’s about all types of inequality in the sports world, including race, colonialism and sexual identity, in addition to gender.

There’s also a lot of important historical context here. The players used to very much be the proletariat. They didn’t make shit. Owners could trade them without any say on their part and the players had no recourse. Being a professional baseball players was not a great job. That changed when they formed a…wait for it…union! And when Curt Flood gave up his career to challenge the reserve clause and a lot of other stuff you should buy my book, Throw Like a Girl, Cheer Like a Boy, to read about, because it’s about a lot more than just gender.

Best quote from Karl Marx ever—“In every epoch, the ideas of the ruling class are the ruling ideas.” In other words, we believe what the owners want us to believe. Things like, “Without capitalism, no one would work and society would collapse because we’re all inherently lazy, doo-de-doo-de-doo.” Do not get me started.

Also, fuck Adam Smith.

Like decent internet, should such a thing ever exist.

Thanks for your insights and to David Brown for sharing them. He and I are part of an increasingly disheartened Nationals season ticket package. Is this the real reason the Nats are tanking (lead LTE in Washington Post a few days ago)?:

Opinion: Say goodbye to the Lerners, and thanks for the memories

Barry Svrluga is a thoughtful baseball writer. However, his April 19 Sports column on the Lerners’ likely sale of the Washington Nationals, “Why owning a baseball team is nothing like owning a mall,” missed the giant tax elephant in the room: the roster depletion allowance (RDA).

The RDA is a tax escape hatch baseball owners enjoy for 15 years in which they can write off the massive salaries they pay their players. The Lerners bought the team in 2006. Their RDA expired in 2021 or 2022. So they can’t write off the $400 million-plus Juan Soto wants now or enjoy the $200 million annual estimated write-offs they’ve enjoyed for years. A new owner certainly will.

Nationals fans should say goodbye and thanks for the memories to Ted Lerner. The sale is a fait accompli for tax reasons, not for lack of competitive desire or community spirit. It’s a tiny bit about baseball and a ton about taxes.

Bradford Brown, Arlington

https://www.washingtonpost.com/opinions/2022/04/22/say-goodbye-lerners-thanks-memories/

I have some experience in federal tax policy, but ain’t never heard of no RDAs.

I am reminded of a classic line my law school professor on federal income tax said on the 1st day of class: If you see unusual behavior it is often due to the tax code.

Wow! "Tell us what you really think". Thanks