Thinking about the opposite of the internet

Should we break the internet? And what would we replace it with? What is the opposite of the internet?

What would the opposite of the internet be? This is the question I’ve been meditating on this week. If you’re a regular reader of this newsletter in all its different iterations, you know it’s something I think about a lot. Too much? Maybe. Probably.

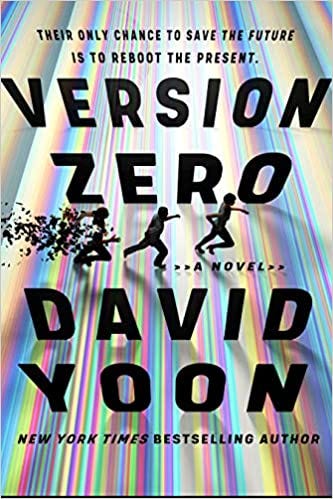

I’ve been thinking about the opposite of the internet this week in particular because I read David Yoon’s new book, Version Zero. The basic premise is that Max, a data whiz, at Wren (aka Facebook) discovers the company is planning to gather and sell personal information about their users to the CIA, NSA, FBI and other shady organizations. When he suggests to his boss that this might be a bad idea, he gets fired, so he and his friends plan a series of hacks to expose the dark underbelly of the internet. Sometimes you have to break things before they can be fixed, they tell themselves, including, maybe, the internet itself.

So, should we break the internet? And if we did, what would we replace it with? What is the opposite of the internet?

This week I also taught one of my favorite theorists in sociological theory—Alfred Schutz. Schutz is a phenomenologist—a philosopher of experience. Among Schutz’s most entertaining concepts is intersubjectivity, or that you know that I know that you know.1 Chew on that for a moment.

A little easier to digest are Schutz’s concepts of umwelt and mitwelt. Umwelt is the realm of directly experienced social reality, the intimate product of face-to-face, co-present interactions. We’re more likely to experience people we encounter in the umwelt realm as “we.” That is, we’re more likely to see those people as like us—complex and fully human.

Mitwelt is (you guessed it) the realm of indirectly experienced social reality. People we experience in mitwelt realms are more anonymous and more likely to be experienced as types. We’re less likely to seem them as like us and it’s harder for us to make guesses about what’s going on in their minds. In fact, we’re less motivated to even try, because they’re “them” and not “us.”

Do you see where I’m going with this? I might know that my cousin votes for a different political party or that my neighbor isn’t vaccinated or that my friend thinks anyone who isn’t an atheist is an idiot. But those people are all in the umwelt realm for me. I know them. I might still think they’re a little crazy. They might, in fact, make me crazy. But they’re still people. Fully human and complex, if also wrong.

But those other people? The ones on the internet? Or described in news stories? Or just the people I imagine in my head but don’t actually know? They’re totally mitwelt. Types, not humans. A Trump voter. An anti-vaxxer. I have no interest in figuring out what’s going on inside their heads, really. They’re “them,” not “us.” Dehumanization comes easy in the mitwelt, is I think part of the point Schutz is making.

The internet seems to be really good at the whole mitwelt deal and trolls are the ultimate manifestation. To do the things trolls do, you have to stop believing that the other people you’re interacting with on social media and websites are actual people. Most of us would never treat people with the absolute disdain that trolls do if we were standing in the same room with them. Yes, some people would, but I still believe that most of us are still better than that. People can still be plenty mean to each other off-line, but the mitwelt of the internet seems to make it a lot easier.

Trolls are just the worst case scenario of the mitwelt that is the internet. And during the pandemic, our umwelt worlds shrunk down to tiny little spaces, as we were prevented from being co-present with each other at all for long periods of time. For some people, we had an umwelt of one. The whole world became full of “those people” who were definitely not like us. I can’t help but think that the anger and rage that are now constantly seething just under the surface of our lives are partly because we stopped interacting with people for so long and still aren’t sure we’re ready to go back to it, or even that we should.

Cool, so umwelt is the opposite of the internet—the intimate, co-present, face-to-face part of our lives. Yes, except. I don’t know, maybe not? This week (it was a busy week) I also read this amazing post from Saeed Jones’ newsletter, Werk-In-Progress, about the friends we make online. Jones argues that his online friendships are just as rich and meaningful and complex as his “real-life” friendships, but we don’t have a language for them. Do you call the person you’ve never met in-person a “friend”? No? Then, what?

Is the person who likes all your tweets, even when no one else does, a friend? What if you can’t even remember why you started following them in the first place? Or the person whose tweets you always like, but who never likes yours back?

Jones’ post is beautiful and insistent that the love you feel for that person you’ve never met, the pain you feel when they tweet or post about their pain—it’s real. It’s love. Just call it love and claim it. “Why can’t this love be yours?” he asks.

Why not? Maybe Schutz got it all wrong. Maybe we can grow and change as humans. Maybe we can make the internet umwelt. Maybe we already have. Maybe we can make the whole freaking world umwelt. I don’t know. I’m not sure. I hope.

Check out this pic from the Substack page! Thanks to all you lovely people, I now have “hundreds of subscribers.” Yes, like 105, but that counts, right? Thanks as always for reading and subscribing and commenting and sharing. Let’s have a conversation later this week about whether or not we should break the internet. And it’s still not too late to sign up for the first winter writing workshop tomorrow! Or one of the three remaining workshops—writing joy, writing habits and writing love. Check it out here.

Intersubjectivity is how social life happens. Communication only works if we are all on the same page and are aware that we are all on the same page. When I ask you to close the door, I have to assume that you know what a door is, but also that you know I know what a door is. This seems basic—of course we all know what a door is—but phenomenologists are interested in unpacking these assumptions that make social life possible.