Yeah, okay, let's talk about yards

And social class and race and the fact that maybe your moral worth is not dependent on the length of your grass.

My second job as a full-time professor came with a three-bedroom house on campus that I rented from the college for…wait for it…$585 a month.1 The house was huge, with a sunroom and a finished basement and a huge yard. The sunroom was amazing (especially for my cat). I never used the finished basement, as it was just me and the cat in this huge house. The yard was a nightmare.

I didn’t own a lawn mower and didn’t particularly want to invest a lot of money in one. With the help of my parents, I ended up buying a push mower. Not one of the self-propelling kind. Oh, no, none of that squishy ease for me. I bought an actual push mower, as in, it took a lot of effort to move that fucking thing around the molehill-pocked yard. Then I proceeded to try and fail to use that little push mower to keep up with the immense expanse of yard.

Eventually during one particularly bad summer, I took a Sudafed for my allergies. This was back when Sudafed was the real stuff that sucked every bit of moisture out of your body. Then I went out to mow the lawn in probably 90-degree heat. Later that evening, I went to join friends at a local bar, took one sip of beer, and passed out from dehydration into the lap of a guy I had recently and very unsuccessfully been dating. This incident pretty much sums up how I feel about yards and mowing.

Honestly, though, my hatred of yards and lawns and mowing goes back way before that. It feels to me like my parents spent most of my childhood during the summers mowing. We had nine acres. Plus a pasture, that for some reason had to be mowed? I mean, it was a pasture. Shouldn’t that mean you don’t mow it? They had a riding mower and a push mower and the sound of my childhood is the sound of those two engines running. All. The. Time.

Not surprisingly, when I moved into the house with a huge lawn, my parents had a lot of feelings about it. Strong feelings.2 The lawn would have to be mowed. And not by anyone but me. It would have to be mowed often. If the grass grew past a certain length, it was a clear sign that I was a complete failure as a human being. This truth was non-negotiable.

My next-door-neighbor, also a professor at the college, was much more laid back about his own lawn. My parents were scandalized. I didn’t want to be like him, did I? The horror.

In Monday’s post I wrote about the shame I associate with gardening. If you let the weeds go, you are a HORRIBLE PERSON. If your grass gets too long…same. This is close to the language my parents and many other people would use to describe someone who doesn’t tend to their lawn in the expected manner. They’re lazy. Or inconsiderate. They’re bad neighbors.

All of this language hides what everyone’s really talking about, which is social class. Yards and lawns and mowing are so inextricably tied up with ideas of what it means to be middle class that I could write a whole dissertation on the subject. No doubt many people have.3

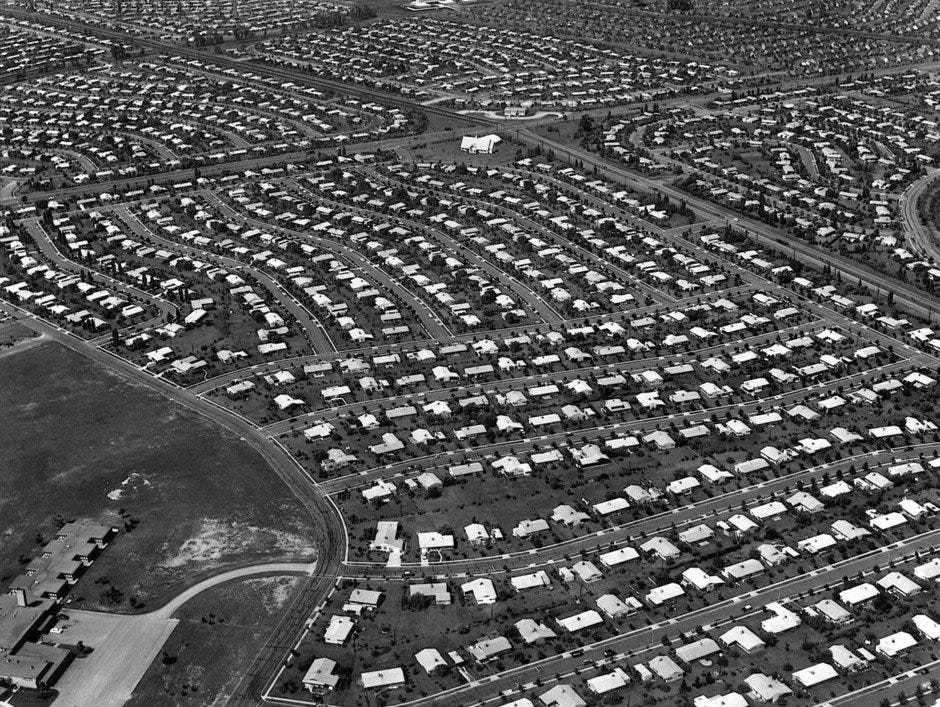

It is, in fact, the tidy yard of green grass that is integral to creating the idea of the middle class in the United States and around the world. In the U.S. specifically, the middle class as we know it was created post-World War II, with the sweeping social welfare policies (yes, that’s what they are) that allowed GIs and their families to get an education and accumulate wealth in the form of widespread home ownership. These policies create the suburbs and with the suburbs, a very specific idea of what it means to be middle class. Detached home. Garage. Dad who commutes to work every day. Mom who stays home. Two kids. Tidy green grass and white picket fence. The American dream is bright green in more ways than one.

And white. It’s almost exclusively white people who were able to access that suburban dream. Black GIs were kept out of the first suburbs in places like Levittown. Which means that the suburbs also shaped and molded our ideas of race. White people are middle class and live in the suburbs. Black and brown people are poor or working class and live in the cities.

For that WWII generation and the next and the next, our yards were inextricably tied to upholding our status as good, middle class, white people. Which shows how identities like social class and race are performative. They’re identities we act out rather than identities that are inherent to who we are. At any moment, if the grass grows too long, you might fall into the dreaded category of ‘white trash,’ losing both your class and racial status. It’s all a lot of weight for a patch of grass to carry.

My parents’ yard (and pasture) were out in the country. From the road, there was no way to see their yard. And yet, it still had to be mowed. It still had to be maintained. This is the power of these identities and social systems. There were no consequences for letting the grass get too long. No one could see it to report them. They weren’t part of a neighborhood covenant, as many people in suburban developments are. They patrolled themselves. That’s the strength of the connection between yards and social class and race. It becomes a moral issue. People who don’t mow their yards are HORRIBLE PEOPLE. They are not like us.

Not long after my mowing-induced fainting incident, I hired a lawn service. This was disappointing to my parents, but better than the shameful alternative of letting my lawn go wild. That I couldn’t take care of the lawn on my own was a personal failing. As soon as I could, moved to a house in downtown Madison with a patch of grass about the size of four yoga mats. Over the years, we’ve dug up more and more of that grass, replacing it with raised garden beds.

The raised beds look okay. My husband recently replaced the first versions with a construction made of corrugated tin, which is all the fashion. They don’t look as neat and orderly as a well-mowed yard, though. And the remaining grass we do have is mostly clover and violet at this point.

As some of you wrote in the comments on Monday, there is a movement away from the perfect yard. One of my favorite houses in downtown Madison has raised beds planted in the hell strip (stolen from Boaz Frankel’s gardening Substack,

bound, and used to describe that no-person’s-land between the sidewalk and the street in urban environments). I love walking by to see how their chard and squash are doing. I love the chaos of it and the use of a space that would often be filled with grass. Which would then have to be mowed.I’m glad there’s a shift in how we think about our yards and how they reflect who we are. The suburbs gave us a lot of toxicity, both in terms of racial segregation, but also the environmental consequences of the way suburban development uses land (which is to say, very inefficiently).

So here’s to wild, unruly yards. Here’s to yards that haven’t been mowed in months. Here’s to yards that have never been mowed. Here’s to judging our moral worth by the things that matter and not by the length of our grass.

Things to check out if you’re interested in yards and mowing and social class and related topics:

I love a lot about Becky Chambers’s Monk and Robot series, including the post-apocalyptic future she imagines, which is actually pretty nice. On this planet, humans take 1/3 of the landmass for themselves to live on, mostly in dense, urban settlements. The rest is left to nature. Not to farm or exploit. Just to be. Well, to nature, and to the robots, but if you want to learn about that, read the books. They’re lovely.

My dissertation was all about suburbs and community which means I did a lot of reading on this topic. But also, I had to get to the whole data collection part, so I couldn’t read everything. Kenneth T. Jackson’s classic history of the suburbs, Crabgrass Frontier, was in my bibliography, but I didn’t have the time to spend with it. It’s a great intro to the history of suburbanization.

The best documentary I’ve seen on race and the suburbs is the third episode of PBS’s Race: The Power of an Illusion. It’s called The House We Live In. Here’s an excerpt from that documentary.

As I did my dissertation research, I came upon the concept of new urbanism. Interestingly, it’s about creating community spaces that are more like Madison. Dense. Built to human scale. Mixed income, which is the hard part, even increasingly in Madison, which is experiencing its own gentrification. But still interesting for thinking about other ways to organize our physical spaces.

Cheap, yes, but also I lived 48 miles away from the nearest Target. Still do, though next month, we’ll be getting a T.J. Maxx and a Kohl’s. Civilization!

I don’t meant to beat up on my parents here. They inherited all these ideas about yards and moral worth from their parents. And, of course, once those norms are established, they’re hard to step out of. We work within the system we have and within that system, they were doing their best. Also, I find myself, not surprisingly, sometimes channeling these ideas unreflectively, too, side-eyeing a neighbor’s unruly yard, before I catch myself. De-socialization is hard.

When I was teaching at Birmingham-Southern College, a student wanted to do an independent study analyzing yard decorations, which was just fascinating. Sadly, I left before I could work with her, but there’s so much there to say JUST on the subject of yard art. What’s seen as tacky and what’s not. The delicate line between too much yard art and just enough. Someone in downtown Madison put two big stone lions in front of their house and it was all anyone could talk about for months.

This is good stuff, Robyn, and spot on in so many ways.

Where I live here in the arid Intermountain West, lawns aren’t a thing. In my very rural county, people are judged by their winter wood stacks. The type of wood, the craftsmanship of the stacking, and the quantity of wood. Folks with lawn longings have a tough time fitting in here.

And if you have some small success growing a lawn, the elk paw through the snow and eat it in late winter.