This is not a post about Glennon Doyle

It's about Van Gogh, or really, like all things, it's about me

If you weren’t around last week, yes, I’m still on my Van Gogh obsession and I’m not even close to done. Also, if you are not up on the latest Substack drama, here’s a brief summary (or check out here) for context. Glennon Doyle, author of Untamed and wife of Abby Wambach, joined Substack. A lot of Substackers got upset, I guess at the way Glennon Doyle joined Substack? Glennon Doyle then left Substack. Trust me, it’s a whole thing, but this isn’t about Glennon Doyle, anyway, so you’re good even if you have no idea who she is.

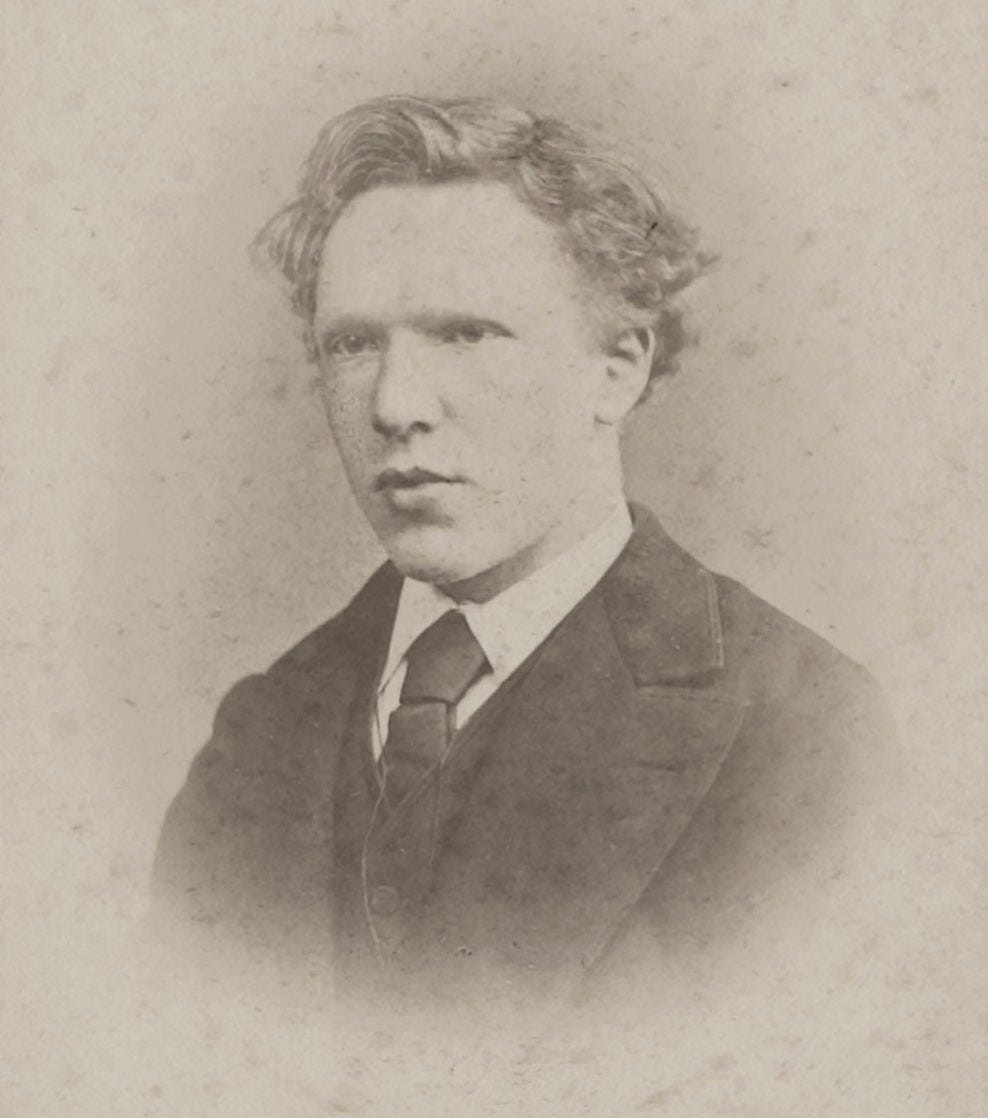

Vincent Van Gogh decided he wanted to be an artist at the age of twenty-seven. Ten years later, he died. The whole of his artistic career lasted ten years and for those entire ten years, Van Gogh sold one single painting. His art got reviewed once. It was not a good review.

Van Gogh knew what art kind of art people liked. He knew what would sell. He knew this because his very first job was working at a very famous dealer in artistic prints. Granted, he didn’t keep that job for long, but he spent a lot of time looking at prints and he knew which ones people bought. After that, his brother, Theo, also worked for the same famous dealer.

Both Van Gogh brothers, as well as several uncles and other relatives, were all enmeshed in the art world of the late 19th century. Van Gogh was lots of things, but ignorant of what art was popular in his lifetime was not one of them.

For the entire ten years of his artistic career Van Gogh’s brother begged Vincent to paint something—anything—that someone might want to buy. Friends, Van Gogh mostly could not.1 The Potato Eaters is a great painting, but not really something anyone in that time period wanted hanging in their living room (maybe still not something you’d want hanging in your living room?).

Van Gogh was conversant with all the latest trends in painting. He’d totally missed impressionism when he was in Paris the first time around (he was still obsessed with religion at that point), but he caught up eventually. He knew Toulouse-Lautrec and Pissarro. His brother put on one of Monet’s first shows. We all know about his fraught relationship with Paul Gauguin.

Van Gogh flirted with impressionism and pointillism and symbolism and japonisme and cloisoinissm. Some of his paintings look like something Seurat might have painted. He straight-up copied a portrait Gauguin did of a woman in Arles, trying to master Gauguin’s style of portraiture. He loved the colors in Delacroix. He thought that just as Monet was known as the artist of Antibes, he could become the equivalent for Arles.

Van Gogh was aware of what it took to become a commercially successful artist. He was aware of all the trends. In the end, though, he mostly did his own thing.

I started this newsletter in August of 2021. I’d been an enthusiastic blogger back in the 2010s. I had no real idea what I was doing back then except writing things and putting them out into the world. When I hired someone to do some actual design and webhosting, I remember him saying, “Wow, your numbers are pretty impressive.” But I didn’t really know what he meant. I was just writing and sometimes also doing blog hops and all the other fun stuff bloggers did back in the day.

A little over a year into the pandemic, I thought it might be fun to get back into that. A friend told me Substack was where all the writers were going. So I started this newsletter with 49 subscribers. As I’d done when I was blogging, I wrote about whatever took my fancy that week. Posts about the writing life. Posts about books. Posts about teaching. Posts, of course, about the pandemic. A lot of those early essays were about me processing my trauma.

I thought, of course, about getting more subscribers. I dreamed of some miracle in which I would get enough paid subscribers to quit my day job. Or maybe at least pay for a nice vacation. In those early days, Substack promised that it was reasonable to expect about 10% of your total subscribers to be paid (lol). With that math, if I could get only 1,000 subscribers, I could make about $5,000 a year from my newsletter. That was doable, right?

If there was a window in which that was an easy thing to do, I missed it. Four years later, I still haven’t cracked 1,000 subscribers. Nowhere near 10% of those are paid (closer to about 3%). I spent some time thinking about how to convert more subscribers to paid. What amazing content could I put behind a paywall to entice them? What extra perks could I promise them? But it all felt…gross to me. I absolutely believe that artists, including writers, should be paid for their work. I absolutely respect and admire other folks who make getting paid on Substack work for them. I just couldn’t find a model that felt right to me. If I put something behind a paywall, all it meant was that only thirty or so people got to read it.

Also at some point along the way, I read an essay in which someone described using their newsletter as their writing lab. It might have been Emma Gannon. I don’t remember anymore, but the idea made immediate sense to me. This newsletter was my playground. My scratch piece of paper. My doodling. Half the time, the essays I write are mostly me talking to myself and I figure, “Maybe other people might like to listen to this conversation.”

I have read some of the endless posts about how to grow your newsletter. I’ve read a few of them about how to make more money. I know that the first step would be to specialize. The first step would be to build a definite brand. My newsletter is, quite frankly, all over the fucking place. I mean, right now I’m in the middle of a full-on Van Gogh obsession. Next month, I’ll be onto something completely different.

This is how my brain works, for better or worse. When I think about writing about the same topic over and over again, a little part of me dies. When I think about picking one topic and sticking with it, it all starts to sound very much like, you know, a job. I already have a job. This newsletter is not a job.

I’m not an idiot. I can see what it takes to write a more successful newsletter. I’m just not much interested in that. I’m okay over here, doing my own thing.

I like Glennon Doyle. Her podcast sustained me through some of the worst days of the pandemic. It was on one of her episodes that I first heard the phrase “emotionally immature parent,” which became something of a revelation for me. I like the way she lays bare her own struggles in the hopes that maybe other people will benefit. It’s a generous thing and not everyone can do it.

There are periods in the last four years of writing this newsletter that I’ve become very enmeshed in Substack drama. Once Notes came into existence, that drama became harder to resist. There is a lot of talk about Substack on Substack. Every few months, someone decries how much the vibe has changed. There have been moments when I’ve thought the best possible thing for my mental health would be to get the fuck off of this ride.

Then I remember what I’m here for. To play and maybe to share that play with some other people. If I can ignore everything else, that seems well worth it.

I am, luckily, not dependent on this newsletter for my income. I write essays sometimes that I’m absolutely certain no one will be interested in. Sometimes I’m wrong. Sometimes I’m not. I don’t much care. Glennon Doyle being on Substack or not didn’t make even the tiniest bit of difference to any of that.

Of course, I see the many, many posts where people celebrate or bemoan their subscriber numbers. This used to bother me some. Now I mostly find it amusing. I have what might be the slowest growing newsletter in the entire history of newsletters. That’s absolutely okay. That’s kind of an accomplishment in and of itself.

Van Gogh spent a lot of time thinking about the structure of the art world and art as a business. At times, he dreamed of a system in which patrons (like his brother, Theo) would support artists while they made their art, removing all concerns about money and how to live in order to leave room for nothing but the art. Maybe this was wishful thinking on his part as he was a constant financial drain on his brother. But he also very much thought of he and his brother as partners in this artistic endeavor.

He also toyed with ideas for bringing art to the masses more cheaply. He played with lithograph. He wanted to make paintings that regular people would buy and enjoy. If Substack or Instagram had existed when Van Gogh was alive, I’m pretty certain he would have been all over it. Also, he would have had like twenty followers and would get into arguments with every single person who commented on his work.

Of course, when the art of other people sold and his did not, Van Gogh felt all the things you would expect him to feel. Angry. Bitter. Jealous. It didn’t stop him from making his weird, weird paintings.

Maybe those weird and glorious paintings were the only thing he could do. Maybe there’s nothing brave or admirable about Van Gogh painting these largely unsellable images. Maybe dude was just so broken or strange that he could never have done anything else. One of my favorite stories is from when Van Gogh joined a studio led by Fernand Cormon in Paris. It was a prestigious studio, including artists like Toulouse-Lautrec and Emile Bernard. Cormon wanted his students to strictly copy the figures they saw—none of the shading or hatching that Van Gogh, who was self-taught as a draughtsman, so loved. Van Gogh tried and tried, but what emerged on his easel were figures with “broadened buttocks, misaligned limbs, crooked faces or quivering contours.” Was that lack of skill or stubbornness or just the way his brain worked? Does it even matter?

Van Gogh was, of course, human. He spent a lot of time thinking about why no one liked his art. He also just kept fucking making it. He kept making it at an astounding pace. He was a fast painter. The people at that same studio in Paris made fun of his fast and furious style. He attacked the canvas. He was capturing a moment and it seemed like he had to do it quickly or not at all.

But he was also prolific. Madly prolific, which is why there’s a Van Gogh painting in so many museums around the world. Despite a career that only lasted ten years, Van Gogh produced over 900 paintings. That’s not counting his ink and pencil drawings. Dude was a madman. He just kept going and going. He painted from the hospitals where he was institutionalized. He would not stop. Maybe he could not stop.

Can you? Can you stop? Do you want to? Van Gogh’s life was not a happy one, but he loved painting. He loved it and he hated it, which is how it goes. But he didn’t stop. He’d been out painting twice on the day he died.

I don’t want Van Gogh’s life, but, fuck, do I want that drive. I want that single-mindedness. I want that confidence to just keep doing what I’m doing, no matter what.

In periods and especially toward the end, Van Gogh did paint subjects that were more commercially appealing, especially landscapes and flowers. But even then, he wanted to be a figure painter. And even then, his landscapes and flowers were weird compared to what people were buying.

Yes to all of this!

“There is a lot of talk about Substack on Substack.” lol and WORD. Yes to the drive! Yes to not being able to stop! Yes to people who share in the hopes it will benefit others. Thank you for sharing your VVG funnel(s) of obsession ✨ I’m enjoying the swirls! 💗