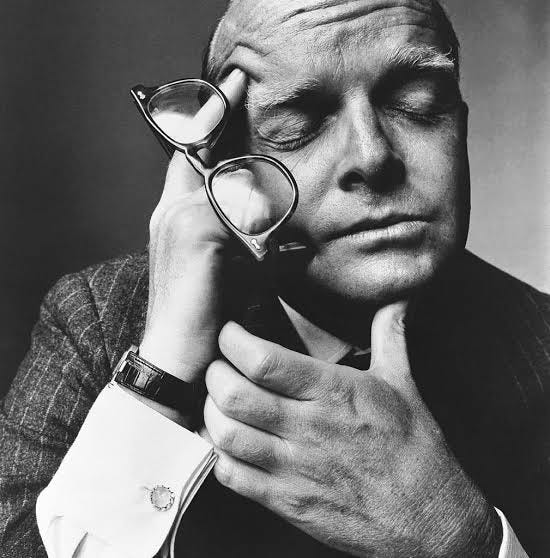

"What did they expect? I'm a writer, and I use everything."

Some thoughts on Feud, Truman Capote, the Swans, and being a writer

My favorite moment so far in Feud: Capote vs. the Swans is early on, after Truman Capote has published the famous story that is a thinly-veiled account of the lives of the Swans and they’ve begun to exact their revenge. He’s talking to someone about the Swans’ reaction (rage and ostracization) and he moans into the phone, “Who did they think I was? I’m a writer.”

If you haven’t watched the series on FX (streaming on Hulu) it focuses on Truman Capote’s relationship with a group of rich New York socialites, who he nicknamed the Swans. The women (at least the ones who are the main characters in the show) included Lee (Jacquelyn Kennedy Onassis’ sister), C.Z. (Gloria Vanderbilt), Slim (whose many marriages included one to British royalty, making her Lady Keith), and his favorite, Babe (the wife of William Paley, an executive at CBS).

In 1975, Capote published an excerpt from his “novel-in-progress,” Answered Prayers, in Esquire. The story laid bare all the sordid details of the women’s lives—including infidelity and murder—and they, as we’d say in a novel of manners, cut him. They expelled him from the high society New York world where he’d become a regular feature. Depending on how you see it, this plunged Capote into a tail spin of drinking, drugs, and bad relationships from which he never recovered. The novel was never finished. Capote died in Joanne Carson’s house (Johnny’s ex-wife) in California in 1984 at the age of 59.

The series is interesting, though it’s not as good as the first season, which focused on the famous feud between Joan Crawford and Bette Davis. As a writer, there are some interesting things to think about in the show and in Capote’s life.

- Capote really did over and over again express his bewilderment that the women didn’t realize he was a writer and understand what that meant. To Joanne Carson he said, "But they know I'm a writer. I don't understand it." To Lee, one of the Swans, he said, “But I’m a journalist! Everyone knows that I’m a journalist!” Also, "What did they expect? I'm a writer, and I use everything. Did all those people think I was there just to entertain them?"

Clearly, yes, they did think he was there to entertain them, as a sort of gay, artist mascot or pet. I imagine for people like the Swans and their husbands, they assume most of the world exists to serve or entertain them in one form or another.

There’s absolutely nothing shocking about the gossip Capote revealed in that story. Scratch the surface of any community and there’s infidelity and, yes, murder. In my own small town, there were so many rumors about which children belonged to whom, it was hard to keep track.

People are complicated everywhere and they lead complicated lives. The only unique thing about the Swans was their sense of power and privilege. They believed that no one would dare to tell their secrets to anyone outside their circle. Within their circle, nothing Capote wrote was really a secret. They were surprised that someone both penetrated their exclusive social clique and then dared to describe it to the rest of the world.

- Was it wrong in some way for Capote to use the Swans’ secrets like that? That’s a question I struggle with as a writer. If you write, you are inevitably telling someone’s secrets, even if they’re just your own. I’ll admit that telling my own secrets is one of the most delightful things about writing. I can take my deepest, darkest thoughts and put them in the head of one of my characters and send them out into the world with no one the wiser. It is deeply satisfying.

But what about other people’s secrets? The first short story I ever published began with a sentence which I’d heard repeated second-hand and which I could not get out of my head. I built a story around that sentence and I was so excited when the story got accepted. That excitement was immediately followed by gut-wrenching dread. What if the person whose sentence I’d taken read the story and recognized themselves? It was someone I knew. Would they confront me? Would they be angry?

Nothing ever came of it but I remember the fear. I still experience it when I think about the short story collection I’m currently sending out, as the material is drawn from my life in the small town where I currently live. It’s entirely possible that people might recognize some fragment of their own lives in the stories. Will they react like the Swans? Will I be cut?

Capote also at one point told someone that all the women in the story would be too stupid to recognize themselves. And, in fact, one of the women, Babe Paley asked a friend if she thought one of the characters was based on her husband. Babe wasn’t sure, while the friend had no doubt. Our potential for self-deception is large.

I haven’t read the Capote story which forms the focus of the show yet. There’s no way to tell how closely he stuck to his source material. He changed names, but barely. One of the women sued Capote for libel, but the suit didn’t go anywhere. To sue a fiction writer for libel or defamation you have to walk a tricky line, proving that the fictional version is truly you but also includes lies. That anyone ever wins one of these cases is a small miracle.

In my own writing, I might start with a real incident or event, but that’s not where I end. Things change in the writing. I have no access to the inside of other people’s thoughts. I have to make those up. In the making it up, the person in my story becomes someone different.

But also, what are secrets? In the case of Capote and the Swans, they told him all their gossip. They seemed to make very little effort to disguise their dirty laundry from Capote. Is it really a secret once you’ve told someone else, let alone more than one person? Is it reasonable to expect anything to be a secret, unless you lock it away inside your head forever? Capote wasn’t their priest or their therapist. What moral obligations did he have?

- You can probably tell that I don’t have a lot of sympathy for the Swans. Capote had just written a very, very famous true-crime account—In Cold Blood.1 Did it not maybe occur to the Swans that they might also become the subject of a book in the way the people of Holcomb, Kansas, had? Or did they think they were above that?

I can’t say I have a lot of sympathy for Truman Capote, either. He was a writer potentially at the peak of his career. When I read In Cold Blood, the book blows me away every time and I’m not a true-crime person. Yes, he invented that genre but he also transcends it. It’s just an amazing book. Period.

He had an advance from Random House for the next book that started at $25,000 and climbed eventually to a million. This was in the 60s and 70s. The whole world was waiting for his words. He squandered all that on booze and drugs and worrying about what a bunch of fairly uninteresting women thought of him. What a waste.

I know, I know. He had his demons. His mother who often abandoned him. His sexuality. His jealousy over his friend, Harper Lee’s, success with To Kill a Mockingbird. He had all of that plus all the other demons that every writer has.

In one episode, James Baldwin appears to Capote, magical negro-style, to give him a pep talk about getting back to writing. It’s fairly ill-conceived and I think James Baldwin would find it deeply insulting. The only part of the episode I agree with was Baldwin urging Capote to get back to writing. Urging him not to waste that talent and fucking opportunity. Yes, I want to scream along with Baldwin. Just write the fucking book!

I don’t know, as a person who wanted nothing more than a steady, unpretentious writing life in which I get to churn out one book after another in the steady knowledge that they’ll make it out into the world, watching another writer squander that precious chance makes me insane.

- Finally, what I take away from the show and Capote’s life: as a writer, you should choose your friends well. Did the Swans really love Capote? Did he really love them? I don’t know. It was no doubt all twisted in the conditions of their relationship, which started after Capote was already famous.

Harper Lee knew him back in the day, when he was just a really weird kid in Monroeville, Alabama. I can totally see how someone like Capote would rather see the version of himself reflected in the Swans over the version of himself reflected back at him from Harper Lee. If I’m very honest, there’s a narrative buried deep inside my head about how my life would be different if I were a famous writer. Part of that narrative is that I would have to care less. All my anxiety about going to social gatherings would disappear because I would be FAMOUS and that’s what people would see.

I know this is a fantasy, as in, it is not true. Look at poor Truman Capote. Becoming famous did not in the least make him feel like he had to perform any less. It might have made him feel like he had to perform even more.

Maybe I just like a good buddy story and so that’s what makes me sad about the fact that Capote’s friendship with Harper Lee fell apart. By the time Capote died, the two hadn’t spoken for years. What would have happened to Capote’s life as a writer if that friendship hadn’t ended? Would Lee have finished her own true crime book? Would Capote have drank less or used less drugs or gotten out of the destructive relationships he cultivated? Would Answered Prayers have been his final masterpiece? Who knows?

At any rate, should I ever become a famous author, I will not be befriending any socialites, New York or otherwise.

This week I read

’s post about non existent jobs she’d be really good at. Like her, I’m also a decent parallel parker. I’m an exceptional watermelon-picker-outer. In fact, I’m good at picking out a lot of produce. I excel at napping, too.I also read

’s thread reflecting on what “free” means, in several contexts, including free labor. It made me think about how people find it perfectly acceptable to pay visual artists for their work, but not so much writers. No one expects painters or sculptors to give their work away for free. They’re quite willing to pay someone to design a logo or a poster. But suggest to them that writers should also be paid for their work and there’s some definite skepticism. Anyone can write, right? Why should I pay someone for that?Anyone can write, more or less, just like anyone I guess can draw. But it’s not all quite the same quality, is it?

I don’t know why people think writing isn’t worth paying for. Because it’s a relatively low-cost activity? I don’t have to pay for paint or canvas and I’ve heard people doing a sort of calculation when they’re buying art—how big is the canvas? How much oil paint did they use? Which is, you know, sort of stupid, but I guess makes a kind of sense.

On the other hand, I don’t have to pay anything for my computer. I already owned it. Paper is cheap. So are pens.

I don’t know. It’s a puzzle and I can’t spend too much time thinking about it. I have writing to do, for which I will mostly not be paid. So it goes, but you can also see why I’m so mad at Truman Capote for leaving a million on the table.

If you would like to pay me, you could become a paid subscriber (I’ve lowered the price to $30 a year) by hitting the button below or you could buy one of my books here.

In an interesting sidenote, Harper Lee, who Capote hired as his research assistant while he was writing In Cold Blood, later suggested that Capote played hard and fast with the facts when he wrote the book. She would know what was and wasn’t true as she was there in Kansas, interviewing the people. It’s interesting to think that Capote lied in his nonfiction and told the truth in his fiction. Writing is complicated. So is the truth.

Correction: William Paley was the founder and longtime chairman of CBS.

I’ve been using my Truman Capote voice as my inner monologue off and on since we talked about this the other night.

It’s been a maddening week. 😂