Sometimes we have to break the world into the smallest possible bits in order to really see it

Van Gogh's perspective frame and writing a novel (or not) and other stuff

I am now two months into my solid Van Gogh obsession. This is my fourth post in this series. Check out the others below. I just finished a biography of Georgia O’Keeffe, so I might be moving on to her. She makes an interesting contrast, in that she experienced a great deal of success in her own lifetime, while Van Gogh did not. And where Van Gogh was desperately seeking community and family, O’Keeffe was often just as desperate to escape it.

Anyway, thanks to everyone who has reached out to say they’re enjoying these essays, especially Joe, who stopped on the street outside the coffee shop to talk about the nature of talent (like in music, are timing and rhythm and having an ear something you can learn, even late in life?).

So much of painting or drawing is learning to unsee the world as you’ve always perceived it and then, if you’re one of the great ones, learning to unsee it once again.

Pick up a pen to draw a tree and what most of us will probably produce is an image of what our brain tells us that a tree looks like. A trunk. Branches. Leaves. Maybe bark. We will draw the representation of a tree and not an actual tree.

If as a painter you want to paint a realistic image of a tree, you have to first throw out that version your brain calls a tree and instead learn to observe the collection of lines and shadows and shades of color that is an actual tree.

If you’re like me and you’re attempting this—to faithfully record the collection of shapes and lines in front of you—it never seems quite like it will work. You step into the unknown, a place where a tree is no longer really a tree. It’s hard to believe that these strange lines will become a tree.

But if you work at it and are faithful to obeying the dictates of what your eye actually sees, a miracle occurs. A tree emerges. An optical illusion. A three-dimensional shape on a two-dimensional surface. Magic, in other words.

Or call it perspective, if magic makes you uncomfortable (also, sorry if magic makes you uncomfortable, because that’s sort of sad). Perspective. The sense that you can walk into a painting or a drawing and take up residence there. It’s not an easy trick to pull off. Depending on who you ask, it took humans thousands of years to figure out perspective in drawing. Although, there’s also the possibility that maybe for a long time and in many places, the realism that perspective implies just wasn’t important. Artists were more interested in portraying hierarchy or spirituality. Who cared about making the horse look real?

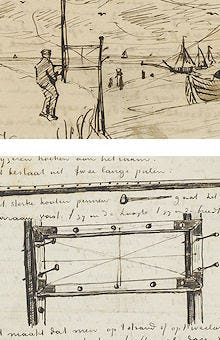

Either way, perspective isn’t an easy thing. It’s not surprising that Vincent Van Gogh felt like he struggled with perspective. There are, after all, mathematical formulas involved if you get very serious about perspective. Van Gogh, in his mostly self-taught, ten-year, crash course in art education, was elated when he found a “shortcut”—the perspective frame.

The perspective frame is a fairly simple device. A wood frame is strung with string in various configurations. Hold the frame in front of a landscape and the string divides the trees and the hills and the fields into small pieces—quadrants or rectangles, depending on how the frame is configured. You draw each individual square or triangle rather than the whole picture at once. Focusing on the parts rather than the whole allows artists to better conquer perspective.

Van Gogh fell head over heels in love with the perspective frame. He had a blacksmith make him a portable version (at great expense to his brother, Theo, of course) which he could take with him into the fields and the beaches. He was especially excited about being able to set up his perspective frame on uneven surfaces, like sand or rocks.

As Van Gogh wrote to Theo, the frame created a “window” out of which he could see and paint the world. It was, for Van Gogh, a game-changer.

A writer friend of mine once described writing a novel as like swimming across the English channel. At night. With sharks in the water. And perhaps, also, missing an arm and weighted down with a small appliance. It is a big task, in other words.

Of course, as Anne Lamott tells us, a novel is written bird by bird. Word by word. Sentence by sentence. You can know that, but also—the water! The waves! The sharks! The darkness!

There are tools to help. There’s one software program called Scrivener. It allows writers to keep all the bits and bobs that are a novel in one place. The chapters, but also character descriptions or ideas or research. It’s all in one big file, which is brilliant and also provides a sort of virtual corkboard, so you can easily move things around. It is so smart and so useful and I am scared to death of it.

I have used Scrivener to write several novels, including my young adult novel, FAIR GAME. With Scrivener, I could easily see where I was in the process. I could create a placeholder for scenes before I ever wrote them. I knew where I was going. It was very organized.

When I sat down and opened up Scrivener on my computer I knew that I was WRITING A NOVEL. A big, long, scary NOVEL. I was going to swim the Chanell. It was all mapped out before me.

Like I said, it was all a little bit terrifying.

By the time he took up residence with Van Gogh, Paul Gauguin did not use a perspective frame. I’m not sure if he ever used a perspective frame and I’m not going to look it up because my feeling is, fuck Gauguin. If there are teams (and, yes, there are teams) I am 100% Team Vincent.

Gauguin could also paint from memory or from his imagination. Van Gogh could not. Van Gogh needed so much to see the thing in front of him. He needed to see the person (hence his endless and expensive need for models). He needed to see the fields or the irises. Pay attention to the dates on his paintings and you’ll find he’s always painting in season. Van Gogh cannot paint apple blossoms in August because the apple trees are not blooming in August. Just thinking about the beauty of this make me want to cry.

Van Gogh was always painting a moment. An encounter. He had to be there, in the space with the thing. Fuck Gauguin’s imagination. Van Gogh’s paintings are conversations. They are his dialog with the world around him. I believe this has to be a part of what makes them so engaging and explosive and tactile.

In Van Gogh’s paintings, we are there with him. In every painting, the thing we don’t see but feel is Van Gogh himself, leaning over our shoulders, whispering to the sunflowers or the sailboats or, yes, to himself. He is in the paint, a ghost of a moment preserved forever.

Fuck, yes, of course he needed a perspective frame sometimes in order to break that down and get it onto the canvas. He needed to make it smaller. More manageable. Of course he did.

Wise writers will tell you to just forget the whole WRITING A NOVEL thing altogether. Tell yourself you are not writing a NOVEL, they’ll advise. You are writing a scene. You are writing a chapter. You are writing a sentence. This is such a hard trick to play on yourself, especially when you’re using something like Scrivener, which at least for me, screams at me every time I open it up—YOU ARE WRITING A NOVEL NOW!

The book-length work of fiction that I’m most proud of at this point in my life—that I think is some of the best writing I’ve ever done—was not written in Scrivener. And probably more important than that, I never told myself that I was WRITING A NOVEL. I just sat down with an idea or a character or a sentence and I let the words come. If it didn’t all fit together exactly, that was okay. That untidy mess became SEX OF THE MIDWEST, my novel-in-stories coming in October from Galiot Press.

In writing that book, I broke it down into small pieces. Quadrants. I focused on the kernel of one place or scene or character or idea. I started with something real and then I expanded that moment. I used a sort of perspective frame and, you know, it worked.

I wonder if, at times, Van Gogh felt a little ashamed of his perspective frame. I know he wished, like Gauguin, that he could paint and draw from memory or his imagination. As someone who loves his art, I’m glad that he could not. I think there’s something about his need to be present that makes his paintings what they are.

Van Gogh didn’t always use the perspective frame. The starry night paintings don’t have perfect perspective. The perspective in The Bedroom and Night Café aren’t quite right, either, which is part of what makes those paintings so distinctive. So appealing.

As an artist, you first learn to unsee the vision of the world your brain gives you. You paint a tree as a series of lines and color. You perform that magic trick of two dimensions into three. Then, if you keep at it…if you become great, you unsee that, too. You begin to see something else.

You begin to see that stars are actually whirling cyclones in the sky. You begin to see that a chairs is always more than a chair. You find a way to make paint do something more and you invite people into that world, one that is both less and more real. You master a different type of magic, something more than optical illusion. You create portals to a whole other universe.

The world is so much, for good and bad. For better and for worse. Just the drama in my tiny backyard on a Saturday in May is enough to make you cry. The toad trying to fit himself between the gaps in our paving stones. The robin fledgling that fell out of the nest too early. The squirrel prowling the roofline, still trying to figure out a way to get to our bird feeder. All of that and humans haven’t even really entered into the picture.

It's a lot to get on paper or canvas. Sometimes you have to break it down. Sometimes you have to start small.

Sometimes you have to say, look here, just at this tree.1

What is the magic in writing? How do you stop time? How do you kidnap someone from their own life and hide them away in the pages of a book? How do you invite them to unsee their world and then see it again? How do you ask them, have you ever actually seen a tree or just the version that’s in your head? How do you suggest, ever so gently or forcefully or playfully—that maybe they have no idea what a tree looks like. But, come here and let me show you.

If right now you’re asking, “Hey, Robyn, what’s happening with those novel-in-stories?”, well, thanks for asking. Copy edits are done. The text is out for proofreading. We’re about to start conversations about cover design (very exciting). And we have a new pub date—October 14, 2025. Mark your calendars and keep checking here for pre-orders.

Every I read certain passages in Annie Dillard’s Pilgrim at Tinker Creek, I see trees completely differently. She is the perfect example of a writer literally saying, look at this tree. No, really, LOOK at this tree.

"Tell yourself you are not writing a NOVEL, they’ll advise. You are writing a scene. You are writing a chapter. You are writing a sentence."

In my case, it's more like "you are transcribing an oral history", since I write so often in first person.

Finally catching up on this Van Gogh series! Really enjoyed it and appreciated so many insights and connections to your own work (and the work of creating in general). I especially loved learning that Van Gogh HAD to see what he painted and always painted in season.